Praying with St. Vincent (Fr. Thomas McKenna) A presentation given during the First International Gathering of the Advisors for the Vincentian Marian Youth Association (Paris, July 15-20, 2014)

Praying with St. Vincent (Fr. Thomas McKenna) A presentation given during the First International Gathering of the Advisors for the Vincentian Marian Youth Association (Paris, July 15-20, 2014)

I. Introduction: “Being Invited Into the Conversation”

Let me begin this session on Prayer by asking you to place yourself on one of the chairs that is pulled up to the table at The Last Supper of Jesus. You are three seats over from Jesus and you notice that he’s getting still, as if preparing himself to stand up and say something. And he does get up. Everybody stops talking, realizing he’s going to speak to them. He starts with what we know as His Last Discourse, telling you and the others on this night before he dies all the things that are closest to his heart. (Jn. c 14-17)

But as he comes to the end of his testimony, instead of addressing them, he starts conversing with his Dear Father – and you listen in. “Now they know that everything you gave me is from you, and they have believed that you sent me. I pray for them.” A little later, Jesus says, “I pray…that they may all be one, as you, Father, are in me and I in You, that they may also be in us…” Finally, Jesus says, “Father, they are your gift to me. I wish that where I am, they may also be with me, that they may see my glory that You gave me.” (Jn 17: 6-11)

Notice what is happening here. Jesus is talking with His Father, and when he finishes, he draws you into the same conversation. What he’s doing is widening the circle, so to speak; he’s asking you to come inside it. You’re no longer standing off to the side and listening in; you’re now “in” the conversation, a part of it. You’ve become a part of this exchange that is always going on between the Father and Son.

Your “inclusion” in this conversation is prayer at its deepest. The prayer of the Christian is at its most profound level his or her entering into this intimate back-and-forth between Father and Son. It is, in a manner or speaking, the believer’s praying the prayer the Trinity is praying.

You might ask, where is the Holy Spirit in this? The commentators say that the Holy Spirit is the communication – better, the love — going back and forth between Father and Son. If the Father and Son are the nouns, one writer suggests, then the Holy Spirit is the verb, that is the action between the other two. St. Augustine, for instance, calls the Son “the Beloved,” the Father “the Lover,” and the Holy Spirit the love going back and forth between Lover and Beloved.

And Jesus is saying he wants us to be right there in the middle of it: “Father, I want them to be where we are, You in Me and I in You and all of us in this circle together.”

In this scene, we have a hint of what is happening in Christian, Trinitarian prayer. And this “happening” comes to clearest visibility when we celebrate the Eucharist. There we are taken into Jesus active giving of himself to the Father, and the Father lovingly returning that gift, as poured out in the Holy Spirit.

But there’s something else to notice about this “prayer circle”. It includes not just the Trinity and you, but also takes in everyone else sitting around that table. In that circle, each is affected by all the others inside it. In another way of saying it, the experiences and wisdom, goodness and failings of any one participant are in conversation with those of the others.

Again, the life-history, the struggles, the insights, the triumphs of all the others have an effect on the conversation (prayer) of each one. The doctrine that names this reality we know as “The Communion of Saints.”

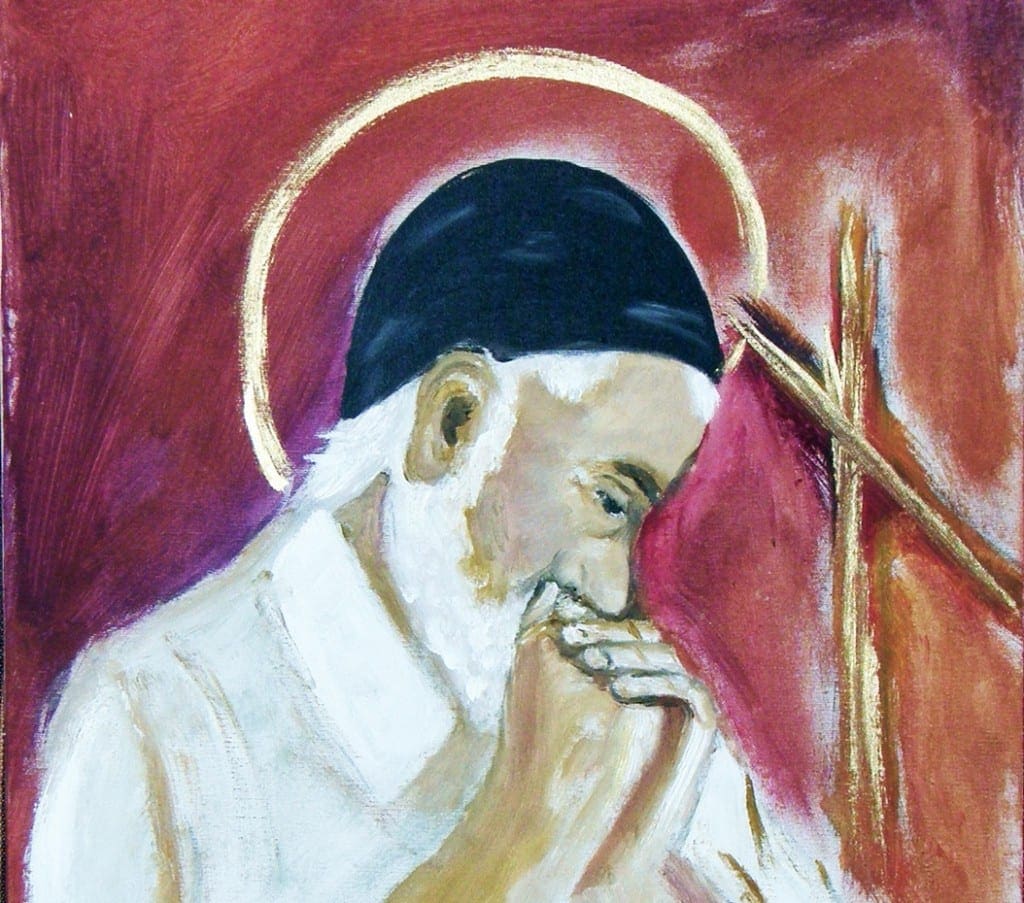

What I want to do for this session is invite one more – special – person into the circle of this conversation. And of course, that’s Vincent. I want to let his life’s experience “get into the conversation,” step into this exchange of life and love going back and forth between all the participants, between all the people sitting around that table.

And so let us do just that: picture ourselves around that table with Vincent sitting next to us. And like anyone else there we open ourselves up to, we allow his attitudes, outlooks, wisdoms and practices to bounce up against our own experiences – and hopefully to shape them. In this talk today, I will attempt to let that happen by following certain themes which were key for Vincent(and which, surprisingly enough, show up in the book!)

2. “Inside the Conversation” With Vincent: (8 Contributions)

1.) The first one is how Vincent would be regarding the character and nature of the main actor in the circle, so to speak, and that is God’s own Self.. Whereas others might associate the Deity with things like distance, fear, judgment, unapproachability, Vincent’s testimony would be to a loving parent, in fact the most caring and solicitous and protecting mother and father imaginable, a parent who has our very best interests always at heart. And so we read in one of Vincent’s letters: “The great secret of the spiritual life is to hand over all we love to God by giving ourselves to all that He wishes, and to do this in perfect confidence that everything will be for the best.” And then the giveaway line for Vincent. “God will take the place of your father and mother. He will be your consolation, your virtue, and in the end the full reward of your own love.” (P. 32 in the English edition of the book Praying with Vincent)

Vincent’s core sense of who God is brings this question to us: inside my circle of prayer, do I sense the warmth and closeness of a parent? Do I experience myself being taken into the arms and onto the lap of a mothering and fathering God?.

2.) A second trait Vincent would bring into this discourse is a high sensitivity to what God wants done, and then going out and doing it. The more technical phrase for this attitude is “seeking and doing the Will of God.” On the edge of many decisions he was about to make, Vincent would so often step back from the issue to ask the question in prayer, “Is this really the course God wants?” But once Vincent came to awareness that some particular move was indeed what God wanted, he would wait no further but would go into action.

There’s a Vincentian writer who holds that the central and characteristic question for Vincent and his followers is this: “What must be done?” This is a “will of God” question, if we could so put it, because it carries within it the two essential qualities for doing the will of God; i.e., the discerning and the acting. For Vincent, discerning without following through with action would not build the Kingdom. But acting without first seeking to find God’s will would open up to all sorts of misdirected, prideful and even harmful results. The God Vincent met in his prayer was a Doing God, a God whose dream, we might say, is to actively build His Reign in this world.

In his rule of life for Priests, Vincent passed on this advice. “A sure way for a Christian to grow rapidly in holiness is a conscientious effort to carry out God’s will in all circumstances…Everyone should show real eagerness in being open to God’s will.” (Praying with Vincent P. 37)

3.) One especially crucial presence in Vincent’s “conversation” is, of course, that of his Lord, Jesus Christ. Early in his spiritual journey, Vincent took the advice of a director who proposed that he look upon Jesus as the one who most perfectly goes about adoring His Father. This image of Jesus looking lovingly into the eyes of His Father provided the context for Vincent’s prayer for a good while. It brought him directly into that Trinitarian conversation, joining his own adoration to that of Jesus as both went about loving their “Abba.”

But as Vincent progressed, that loving worship took on an additional outward directed tone, and that is “being sent.” Vincent became attracted to the scene in the synagogue near the beginning of Luke’s gospel where Jesus stands up and, in the vocabulary of the prophet Isaiah, states why he’s come and what he wants to do. Jesus claims he’s being sent, being missioned by and from the Trinity to proclaim liberty to prisoners and good news to the poor. This gospel event is a key for unlocking Vincent’s distinctive appreciation of Jesus Christ. It explains the high energy that marked not only his many years of evangelical activity, but it is also what made him so insistent that his followers also jump on this sending energy of the Missionary Christ.

And thus his often cited words, so filled with this same dynamism. “To make God known to the poor, to tell them that the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand and that it is for the poor – O how great is that is. It is so lofty a calling to preach the gospel to the poor because that is exactly the very role and ministry of the Son of God”. (Praying with Vincent P. 43)

4.) When we are “inside that circle of conversation with Vincent,” there’s another quality that can flood the space if we let it. And that is trust, trust that God will provide, will take care, will move things along for the best. We call this belief in the “Providence of God.” In the life of many believers, trust is a hard thing to come by, especially when things are not going well and worries are clouding the horizon. Over his lifetime, Vincent’s prayer grew more and more trusting. He deepened in his conviction that God was guiding everything. And so Vincent could both lean back on that guidance, and let it lead him forward.

He visualizes God’s Providence as something like runner who sets the pace in a race. If you run too far behind Providence (by not trusting), you stumble and get exhausted because you’re not tapping into all the care The Father is giving. If you run ahead of it – trusting more in yourself than in God – you wander off in the wrong direction along a path that could run counter to God’s will. More and more does Vincent bring this confidence into his projects, no matter how risky or tenuous the outcome seems. He looks ahead and relies on the fact that God’s care is in front of him. But too, he often looks back and in hindsight catches glimpses of where God has been leading him all along.

To a person who’s fretting over not having enough resources to help feed the poor, he says, “Don’t worry yourself overmuch…Grace, God’s presence, has its moments. Let’s give ourselves over to the providence of God and be very careful not to run ahead of it.” In another spot he says, “We ought to have confidence in God that he will look after us, since we know for certain that as long as we are grounded in that sort of love and trust, we will always be under the protection of God in heaven… We will never lack what we need even when everything we possess seems headed for disaster.” (Praying with Vincent P. 49)

Vincent is telling us to bring more trust into our praying. God is leading the way and to the extent we can lean back into his presence, trusting that His Providence is there, will He lead. Inside that circle, one feels the reality and solidity of God’s constant care.

5) Someone once described the Trinitarian conversation as an energy field. The person praying inside it feels – at least at some level — the force and dynamism coming from the Father and going back to the Father. Inclusion in it is anything but static. Vincent felt this energy; it was what impelled him – or better, sent him out — to bring the good news.

One way to appreciate that impulse he experienced “within the conversation” is to imaginatively place ourselves in that Luke Gospel scene that so fired Vincent’s imagination and got him moving. And that’s the synagogue incident where Jesus is handed the scroll and asked to comment on whatever reading he selected.

To do this I’m going to use a guided meditation right from the book. And you recognize this method as simply another way of stepping inside Jesus’ own prayer to the Father.

So begin by placing yourself in the Trinity’s presence. Then relax your whole body, starting with your feet and coming right up to your head. Breathe deeply and slowly, welcoming in the breath of life and the Spirit of God.

Now follow behind Jesus and his disciples as they walk into the synagogue at Nazareth. A reverent hush greets their entrance. You take a seat in the back row, but you can see Jesus and his motley crew up front. A row of elders sits in the first row. The leader of the synagogue walks up to Jesus and hands him the Torah. Jesus slowly opens it and finds the text from Isaiah that he wants. He rises, looks around at the congregation, takes a deep breath, and then in firm and distinct tones reads these words:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me, for he has anointed me to bring the good news to the suffering. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives, sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim a year of favor from the Lord.” (Lk 4: 18-19).

Jesus hands the Scriptures back to a young attendant and begins to scan the room. His eyes stop and look into yours. Very deliberately he says to you, “Today these words have been fulfilled in your hearing.” Then he walks slowly down the aisle and out of the building.

In the silence, you ponder the words he spoke to you.

Sit there a while and listen for whatever comes into your mind and heart. If it helps, write down what came to you….

The point? Try to experience something of the dynamism and the force of this “sending” Vincent himself experienced.

6) In any number of places in the gospels, Jesus speaks about seeing. Not only does he give sight to blind people, but he often talks about a kind of blindness that afflicts those who can see. His paradoxical way of saying this: “They see without seeing.” When these so-called sighted people look out at their world, they miss many things. For them to break through their short-sightedness, something would have to extend their range of vision to let them see farther and deeper. Isn’t that “extending” exactly what happens to the disciples around that Last Supper table. When they get “taken into the conversation,” their eyes are opened to catch sight (even if only a little bit) of what is really happening between Jesus and His Abba. They are just beginning to see a little further. And they are seeing not only through their own eyes but also through God’s. And for the rest of their lives that vision (of the way things really are) grows ever more acute.

So much of Vincent’s gift to serve the poor has to do with this “extended seeing.” Through both prayer and service, he learned to penetrate past the surfaces so as to spot more of what God sees in the situation. Listen to these words, so often cited as the key to his spirituality.

“I should not judge poor peasants, men or women, by how they look on the outside nor by their seeming mental capacities. All the more is this so, since very frequently they hardly seem to have the appearance or intelligence of thinking creatures, so gross looking and off-putting they are. But turn the medal, and you will see by the light of faith that the Son of God, whose will it was to be poor, is represented to us by just these people.” (Praying with Vincent P. 62)

And even more clearly, “Let us, my sisters, cherish the poor as our masters, since Our Lord is in them and they in Our Lord.” (Praying with Vincent P. 63)

The point? Vincent’s prayer led him more and more to see as God sees, and that is into the heart of things. It let Vincent’s eyes penetrate down to the core of people (especially poor people), which indeed is the precise spot where they are loved by God.

7) With all this talk about being taken inside the Trinitarian conversation, you could get the impression that the main thing a believer does is sit still and silent, then gaze into God, as it were, and do little else. Anyone reading St. Vincent would soon feel his impatience with such an attitude. Though he thought “listening into the conversation” was essential, he also believed it absolutely necessary to put what he was hearing there into action.

For one thing he insisted on hard work, the laboring for God’s Kingdom that goes hand in hand with listening. In a somewhat confrontative letter to one of his followers, he stakes out his ground clearly.

“So very often, this resting in the presence of God, (these outpourings of affection for him, all these good feelings toward the Lord and toward everyone else), though good and to be desired, are suspect if they do not express themselves in a practical love which has real world effects.” (Praying with Vincent P. 67)

In another place, he tells of the long-term effort it took for him to soften a marked harshness in his personality and also to moderate his mood swings. He came to see these traits as interfering with his service of the poor. Looking back at the gap between his intentions and his actual behavior in those days, he confessed:

“During a retreat….I turned to God and earnestly begged him to convert this irritable and forbidding trait of mine. I also asked for a kind and approachable spirit. With the grace of Our Lord — and by giving attention to checking the hot-blooded impulses of my personal disposition –I have been at least partly cured of my gloomy disposition.” (Praying with Vincent P. 72)

The Point? For Vincent, prayer leads to action and action leads back to prayer. You might well say that Vincent “very actively in the conversation…”

8) If there’s one word to catch the flavor of Vincent’s way of sharing “in the conversation,” it would be this one: balance. Sitting at that Last Supper Table, he both listened to God’s words and acted with God’s actions. Impatient on the one hand with fleshless acts of piety that didn’t bring practical results, and on the other with shallow activity not grounded in God, Vincent is a model for how contemplation and action can nourish each other rather than compete. His often cited aphorism, “leave God for God,” touches directly on this. When advising some Daughters of Charity who were having conscience problems about prayer time, he famously wrote:

“If at the time for prayer in the morning, you have to bring medicine to your patients, do it peacefully … Give yourself over to God’s wishes, offer up what you are about to do, join your intention with the prayer that is being made back at home, and go about your task with a clear conscience. If when you return you are free to spend a little time at prayer, all well and good. But you must not worry yourself or think you have failed to keep the rule if you omit that prayer time. It is not lost when you leave it for a good reason. And if there ever was a good reason, it is service of the poor. To leave God for God, that is, to leave one work of God to do another of greater obligation, is not to leave God.” (Praying with Vincent P. 115)

The point? The Trinitarian conversation is made up of an ever revolving cycle of listening and acting. We’re taken into Jesus’ heart both as He speaks with His Father at the table, and as he leaves the table to do the work of the Father in the world. And Vincent’s prayer is a grace-filled instance of how this listening and acting feed and moderate each other.

3. Conclusion

Clearly there are many ways to approach Vincent’s wisdom on prayer. We’ve taken one that brings him into the praying that went on at The Last Supper, that open and inclusive interchange which brought the disciples into Jesus own heart as he offered himself to the Father for our sakes. For sure, Vincent is one of those participants in that ever renewed event. May we, in our prayer around that table, come to know more of the depth of his contribution into this saving conversation?

0 Comments