In “Behavioral Science and the Stress of Poverty: Dan Torrington, SVDP Western Region Voice of the Poor Leader writes “Once we as Vincentians begin to really appreciate the mental and emotional stress of scarcity, as well as the physical toll poverty exacts, we know we have no alternative but to advocate for state and national programs that reduce the stress of poverty.” He roots this statement in research done by behavioral scientists.

In “Behavioral Science and the Stress of Poverty: Dan Torrington, SVDP Western Region Voice of the Poor Leader writes “Once we as Vincentians begin to really appreciate the mental and emotional stress of scarcity, as well as the physical toll poverty exacts, we know we have no alternative but to advocate for state and national programs that reduce the stress of poverty.” He roots this statement in research done by behavioral scientists.

His reflection begins…. “People are poor because they are lazy and don’t want to work.” We have all heard various versions of this simplistic explanation as to the cause of poverty. However, the growing body of behavioral science research indicates that the cumulative stress of scarcity of basic human needs, especially in childhood, better explains long term poverty.

When I joined St. Vincent de Paul and was making my first home visits, I gave little thought to why a person/family was in a dire situation. My focus was the crisis at hand. The thought of poverty as a field of scientific research never occurred to me. Nine years later I have a broader understanding of poverty and know that Vincentians have an important role to play in easing the burden of poverty.

The founder of our Society, Blessed Frederic Ozanam, recognized implicitly that poverty was not a simple issue when he told us “not to be content in tiding the poor person over the poverty crisis.” Frederic specifically urged us to “study their condition and the injustices which brought about such poverty, with the aim of long term improvement.”

Nonfactual explanations of the cause of poverty must not be allowed to go unchallenged. We are called to advocate for the poor. We need to understand the real causes of their condition. What causes generational poverty? Why has the gap between the haves and the have nots been widening? Is “laziness” an adequate explanation or are there other factors at work?

Dr. Ruby Payne in Bridges out of Poverty speaks of poverty as a lack of resources (Financial, Emotional, Mental, Spiritual, Physical, Support Systems, Relationships, Knowledge of Hidden Rules and Coping Strategies). Dr. Payne puts “Financial” as the least critical resource. Dr. Payne’s book is a good start, but there is more we need to know.

An Internet search reveals that there are many behavioral scientists studying poverty. Their work points to the “cumulative stress of poverty” as the reason why families in poverty tend to stay in poverty.

Jack P. Shonkoff, M.D., Professor of Child Health and Development at Harvard University, writes that extensive research on the biology of stress shows that healthy child development can be derailed by excessive or prolonged activation of stress response systems in the body and brain. Such toxic stress can have damaging effects on learning, behavior, and health across the lifespan. http://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/toxic-stress/

Gary Evans, Ph.D., a research psychologist at Cornell University, studies how the physical environment affects the health and well-being of children. He has conducted a 16 year research project measuring how a child’s environment impacts development. His research indicates early childhood poverty is associated with multiple, deep, and long-lasting adverse developmental outcomes.

Professor Evans writes, “One principal pathway to understand the strong, adverse impact of childhood poverty on health and well-being throughout life is excess exposure to cumulative risk factors. The environment of childhood poverty can be fairly characterized as a plethora of suboptimal living conditions. Among the physical contexts of early development in low income homes are: noise, crowding, poor quality housing, inadequate neighborhood settings, lower quality school and daycare settings and excess exposure to various toxins such as lead. Lower income children are also much more likely to live in a household that is highly chaotic, with fewer routines and less structure. Their families are also much less stable with greater adult partner changes, more frequent residential moves, and more variable employment hours of their caregivers. In addition to the physical surroundings, low income children also face more psychosocial demands. Their parents are more likely to divorce, their household often has greater turmoil and conflict, and because their parents also confront many of the same stressors as their children, unfortunately low income parents tend to be less responsive to their children and less able to monitor them as well.

They read to their children less, are less likely to expose them to informal learning opportunities (e.g., library, museum, music or art instruction) and they are often less able to provide a rich, cognitively stimulating home environment (e.g., books, computers, and age appropriate games and toys).”

Dr. Evans concludes that children in poverty have more difficulty self-regulating, are vulnerable to helplessness, and manifest more psychological distress. In each case, these elevated psychological morbidity symptoms are mediated to varying degrees by exposure to cumulative risk.

Eldar Shafir Ph.D., Princeton, studies how deprivation wreaks havoc on cognition and decision- making. Being poor requires so much mental energy that those with limited means are more likely to make mistakes and bad decisions than those with bigger financial cushions. This scarcity mindset consumes what Shafir calls “mental bandwidth” — brainpower that would otherwise go to less pressing concerns, planning ahead and problem-solving. This deprivation can lead the brain to only focus on the most immediate scarcity and ignore other pressing areas of life. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-Y7lcYoFC4

Dr. Joan Luby, Washington University, School of Medicine, writes that research shows environmental factors of poverty appear to be associated with smaller brain volume in areas involved in emotion processing and memory. The research provides insight as to why children who are exposed to poverty at a young age often have trouble academically later in life. JAMA Pediatric. 2013 Dec;167(12):1135-42. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3139.

Once we as Vincentians begin to really appreciate the mental and emotional stress of scarcity, as well as the physical toll poverty exacts, we know we have no alternative but to advocate for state and national programs that reduce the stress of poverty. We must advocate for a living wage, quality child care, enriched early childhood education, mandated maternity leave and simplified registration and renewal for poverty programs. We need to insist that federal and state poverty programs be measured in terms of the cost of added or reduced stress on the poor (not just in terms of the cost in dollars). Finally, we need to make lawmakers aware of the poverty research that is being done by behavioral scientists.

Total federal and state spending for poverty programs in 2016 will be $109.7 billion, 17.6% less than five years ago (2011). There is no doubt that lawmakers are balancing budgets on the backs of the poor. Behavioral science research indicates that poverty is a self-perpetuating condition. Left untreated, the condition will grow and the poor will be an ever increasing percentage of our nation. http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/us_welfare_spending_40.html

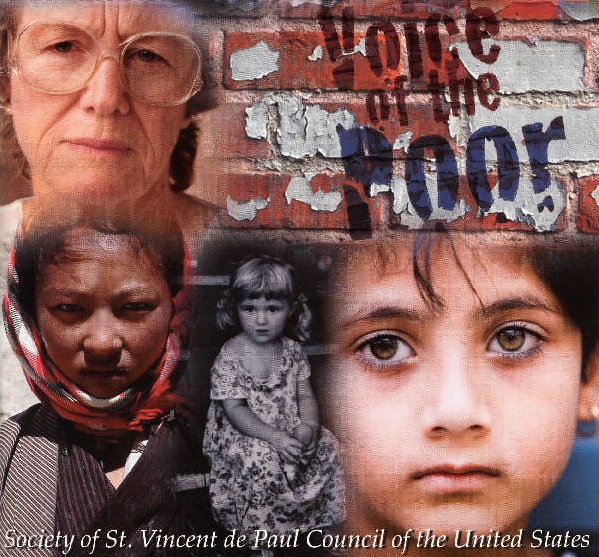

Lawmakers are influenced by large numbers of potential voters. Vincentian voices, yours and mine, need to be heard. When Vincentians speak as a group, we can and do influence lawmakers. Let each of us resolve to use the power of our voice and pen to come to the aid of our impoverished neighbors. We are called to be The Voice of the Poor.

0 Comments