In the spring of 1947, nothing about the future of India, its identity as a nation or the kind of country it would be, was certain. India would soon be free from British colonial rule, but it could not fulfill the basic needs — let alone the hopes and ambitions — of most of its people. That would require new institutions, new ideas, and men and women who were willing to take a chance on building them.

India had been devastated by World War II and then partition, which split the country in two. By the end of 1948, two of India’s cities, Delhi and Mumbai, had each absorbed more than 500,000 refugees, and the country had endured violence, dislocation and food shortages on a mass scale. More than 20 million Indians lived under direct rationing, entitled to 10 ounces of grain a day. That was the period during which a handful of Catholic nuns from Kentucky chose to come to Mokama, a small town at a railroad junction in northern India on the southern banks of the Ganges River, to start a hospital.

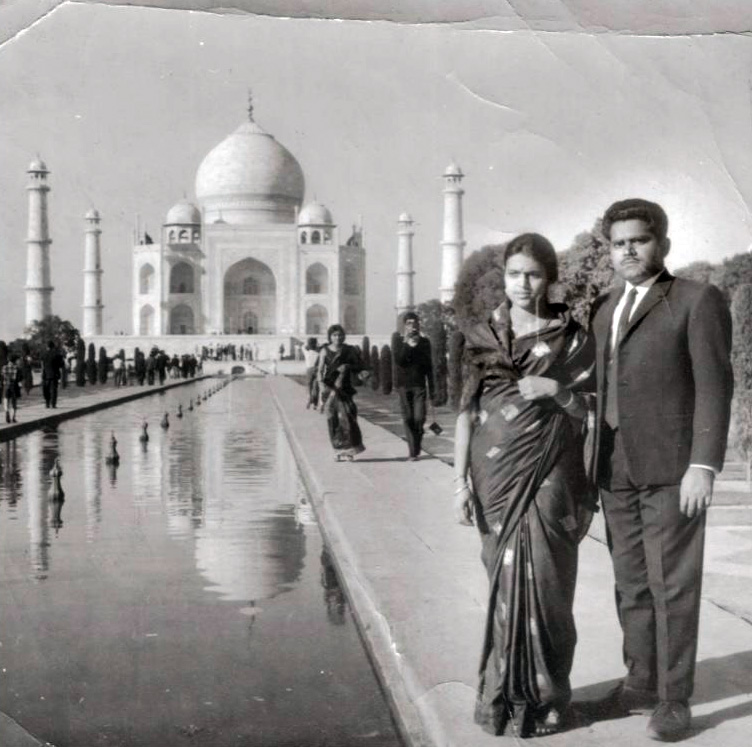

The author’s parents at the Taj Mahal, in February 1971. In the 1960s, her mother studied to become a nurse at Nazareth Hospital. Thottam Family Photograph.

The story of Nazareth Hospital began, for me, as a family story. My mother studied nursing there in the early 1960s, and those skills helped her travel, with my father, to the United States. But this hospital and the women who started it is also a story of a nation in the process of becoming itself. The people who shaped India in those years included outsiders and misfits, the orphaned and the underestimated, foreigners and Indians from many different religions and castes — those whom history rarely remembers.

One of them was Sir Joseph Bhore.

A distinguished Indian bureaucrat who had served the Crown loyally, even as Gandhi’s independence movement gathered force, Bhore retired with a knighthood in 1935 to the island of Guernsey. When German forces occupied Guernsey and the other Channel Islands in 1940, he was forced out of his quiet retirement. With nowhere else to go, he went back to India. In October 1943, the colonial government of India asked him to lead a “broad survey” of health conditions in British India, the first of its kind.

It was the most significant assignment of his life.

Sister Crescentia Wise (in white habit) with a doctor and hospital staff registering patients for the Hansen’s disease clinic. Sisters of Charity of Nazareth Archival Center.

Bhore had presented, in heartbreaking detail, the toll that hundreds of years of colonial neglect had taken on the bodies of hundreds of millions of Indians, and yet he believed, in his technocratic way, that Indians themselves could reverse the effects of generations of cruelty.

The overall goal was simply to increase the number of doctors and other health professionals. There was one doctor for every 6,300 people in India, compared with one per 1,000 in England. He set a target of increasing the ratio to one for 2,000 by 1971, and imagined a network of small village health centers. A pair of trained doctors would be in charge of several villages, serving, with a staff of 36, a population of about 20,000. This was one of the very few moments when someone in the government of India saw with absolute clarity what was required to change India for the better, how to do it and what it would cost.

The six pioneer sisters, soon after arriving in Mokama in December 1947, with the empty hospital building behind them. Sisters of Charity of Nazareth Archival Center.

When she arrived, Veeneman found an empty warehouse, a series of empty rooms. There were no hospital beds, no medicines, no electricity, no source of running water, no doctors, nurses or other trained staff. The sisters’ mission was to turn this building into the tenth Sisters of Charity hospital, and they would have six months to fulfill it.

On Jan. 5, 1948, less than a month after the sisters landed in Mokama, a young woman arrived on their doorstep. She was tiny, not even five feet tall, and had been living with the Carmelites in Patna, the closest big city, for several months. Her name was Celine Minj, and Veeneman offered her a bed on the roof.

She looked at what the sisters called a hospital and was not impressed. There was nothing, just a small hall in a building near the railway station, and a dispensary with a few boxes of medicines. But even so she was a step closer to the life she wanted.

Minj was born in 1933 in the central Indian forests, on the tribal lands of the Oraon people. Her father had died of a high fever when his young wife, Mariana, was expecting, leaving Mariana and her infant daughter at the mercy of their male relatives.

Minj would always be tiny, but she grew tough and strong and intently aware of the difference between herself and the other children in the family, the ones whose fathers and grandfathers had lived. It wasn’t the extra handfuls of rice, however, that Minj envied. She saw the other children going to school, and as soon as she could talk, she gave voice to this hunger: “I want to study.”

Once she was strong enough, Minj would walk next to her mother carrying bricks in a basket on her head at construction sites. Together, they earned enough for tuition, books and pencils. In 1945, as the war ended, Minj was 12 and had finished seventh grade, but her ambition to be educated had begun to cause trouble. Here she was, a young girl, neither pliable enough to be married off nor clever enough to make her way out of her village, so eventually she ran away from home and found her way to Mokama.

When she arrived, Minj remembered those precious days at school, watching the nurses who cared for the boarding students. She could see that same competence and determination in these American women. She decided to stay. Almost immediately, Minj became essential to the sisters’ work. When someone turned up at the dispensary with symptoms the sisters couldn’t comprehend, she translated. When they received the first calls to go out into the village to deliver a baby, she went with them.

Already, by late January, patients were lining up for treatment. But the sisters still had no doctor of their own. Veeneman wrote letters to missions, hospitals and medical schools all over India to find one. The opening date was set for July 19. “Please,” she wrote in one letter home to her family, “redouble your prayers that we will get a doctor by that time.”

On July 24, 1948, days after the opening of the hospital, a young doctor walked into the mission. Lean, strong and quiet, with thick hair that he kept combed in a stylish wave, Eric Lazaro was not their first choice. The same day he accepted their offer, Veeneman got a letter from a woman answering the same newspaper ad. “I am only sorry that we did not get the lady doctor first, because that is what is needed most in our section of the country,” Veeneman wrote in a letter to the motherhouse. But he was as good a substitute as they were likely to find.

Lazaro was born in 1921 to an Anglo-Indian family. When he was 6, his mother died, possibly of tuberculosis. Her death destroyed their young family. His widowed father, an obstetrician, drank heavily and, unable to care for his son, sent him to live on the forbearance of his relatives. As soon as he finished high school, Lazaro started medical school, scraping together just enough money to pay his fees. Once he finished, Lazaro was among those millions set adrift after the end of the war but before independence. Mokama was a nowhere town, but he was a doctor with no experience, and he was ready to leave everything else behind.

As soon as the hospital opened officially, patients began coming every day, a stream of people with cholera and malaria and unspecified fevers, men with infected wounds and women in labor. The mission annals and the sisters’ letters home, which were at first so full of homesickness — Veeneman would sometimes weep while reading letters from the order’s headquarters back in Kentucky — were instead occupied with accounts of the people who came to the hospital, whether they lived or died, and the occasional novelty of a wealthy patient who arrived by motorcar or summoned a doctor and nurse for a house call made by elephant.

The supply of medicines and equipment the sisters brought with them as cargo — antibiotics, penicillin, painkillers, bandages, disinfectants — were usually enough to treat the most common illnesses and injuries. But occasionally they could do little but act as witnesses, for the woman in the throes of a psychotic episode or the baby in the final stages of dehydration.

Lazaro proved himself to be an able and resourceful doctor. In addition to treating the constant stream of infections and tropical diseases, he helped with eye surgeries at a temporary clinic set up by some visiting doctors. He did the autopsy for a beloved orphan boy who had lived at the convent for months but eventually died, his enlarged spleen revealing the toll of malaria and kala azar, a disease spread by sand flies. He managed to operate on a woman with an ectopic pregnancy by lantern and flashlight, and with the help of a visiting surgeon, he operated on one of the nuns, Sister Florence Joseph Sauer, when she had appendicitis.

It was so humid when they opened the hospital that it took days for clothes to dry, and flies tormented them at table, descending over their plates and teacups. There were so many patients, however, that they hardly noticed. The lack of running water did not prove to be a serious obstacle, either: Sister Crescentia Wise set up a still to produce purified water, a contraption that Sister Charles Miriam Holt quipped would not be out of place in the hills around Nelson County, Ky. In August, the sisters began recording their census of patients: On Aug. 7, 19 in the hospital and 61 in the dispensary. By the end of that month, both were overflowing.

Throughout those first few months, the sisters scrambled to find enough nurses. Here, too, Bhore had foreseen their difficulty. The committee estimated that there were about 7,000 nurses in all of India — one nurse for every 43,000 people, in a country of 300 million. “There are not in the whole of India today so many qualified nurses as there are in London alone,” the report noted.

While there were about 190 schools across India where nurses were trained, the standards fell far short of those in most modern nursing schools. In fact, they were not really schools at all. They were simply schemes under which women would work at hospitals without pay, learning what they could on the job and providing free labor to hospitals in the meantime. India’s nurses were almost entirely women, and the Bhore report identified the “deplorable” working conditions as the main impediments to increasing their number.

Veeneman was constantly asking the hospitals in Patna, the Patna Jesuits and other orders in India to send them nurses, even those who hadn’t completed their training. The lack of clear standards for nurses in India became very obvious. One left for a vacation and never returned; another turned out not to be a nurse at all but a compounder, who had worked in pharmacies mixing and preparing medicines but who could not even manage to use a syringe.

So the sisters made do with the people they had. Sister Florence Joseph took over the night shift. Their household staff helped with the patients’ trays and cleaning. Minj was assigned to register patients and help in the dispensary. Her crucial role in communicating between patients and the sisters was formalized, which brought her a step closer to nursing.

But none of these improvised solutions were enough to deliver the standard of care that the sisters expected, so within a few months they started a makeshift nursing school. They set aside a room and some tables and chairs, and the sisters and Dr. Lazaro taught anatomy, first aid, nursing arts, dietetics and the routines of patient care. The first students were three of the haphazardly trained nurses who had landed in Mokama hoping to work — and Minj, whose desire and enthusiasm for nursing had never wavered.

It is hard to overstate the boldness of what the sisters at Nazareth Hospital accomplished within two years of arriving in India. By December 1949, the sisters had made a note in the annals about all the people helping them — the doctor, four helpers in the dispensary, seven nurses, three working in the hospital, three girls in the house, a cook, two kitchen helpers, a water carrier, a night watchman, a handyman who kept the generator running, three hospital sweepers, a gardener and his helper, and the washerman and his family, who handled the endless laundry. All together there were 30 on the list.

It was perhaps not exactly what Bhore had in mind when he imagined 36 staff members assigned to two doctors. But it was close, and the sisters had fulfilled Bhore’s recommendations almost to the letter, setting up a basic primary-care hospital and village health center that devoted most of its resources to easily treated communicable diseases, infant mortality and child delivery, and a school to train nurses.

The nursing school eventually attracted generations of Indian women as students, some of them just teenagers, many of them also motherless or fatherless children. These young women would force the order to examine everything about its work in India and what it meant to be a missionary. After Lazaro, the hospital finally found its “lady doctor,” Mary Wiss, a sister from their order who would have to choose between her religious vocation and her calling as a surgeon.

India has taken many turns inward and outward in the 75 years since independence, and although it remains a proudly pluralistic democracy, that tradition seems increasingly fragile. The hospital has managed to endure through all of this. Its presence, as an institution founded and run by women, stands as a challenge to those in power, a lasting reminder of those early years and that crystalline moment of hope.

By Jyoti Thottam of the New York Times

Jyoti Thottam (@JyotiThottam) is a member of the editorial board. She was Time magazine’s South Asia bureau chief from 2008 to 2012 and is the author of “Sisters of Mokama: The Pioneering Women Who Brought Hope and Healing to India,” from which this essay is adapted.

Source: https://nazareth.org/

0 Comments