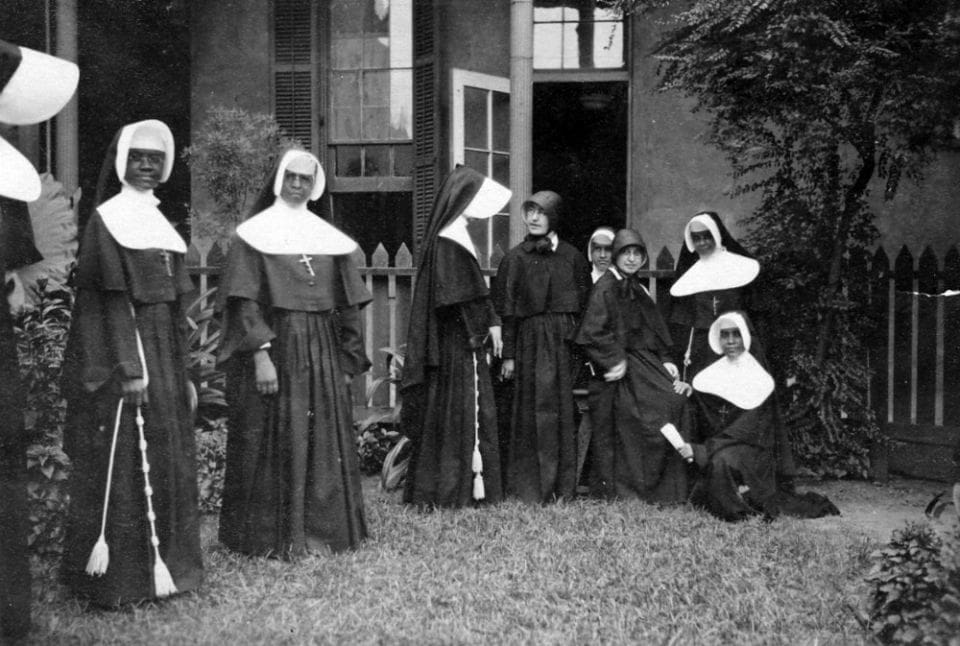

Sisters of the Holy Family, in the white-and-black veils, and Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill, in the black caps, in New Orleans in the 1920s (Courtesy of the Archives of the Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill)

In the 1960s, Sr. Sylvia Thibodeaux moved away from her Black congregation, the Sisters of the Holy Family in majority-Black New Orleans, to attend mostly white Seton Hill University, run by the white Sisters of Charity of Seton Hill in the almost entirely white city of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, about an hour east of Pittsburgh.

“I was a young woman, and I had never been away when I left home to enter the convent. I had never been away from my parents or out of the immediate area,” Thibodeaux said. “So coming to the Pittsburgh area was a real experience for me.”

It was an experience that many sisters from both congregations have shared for decades in a relationship between the two communities that has stayed strong, despite distance and cultural divides, for 99 years.

“One of my teachers, Sr. Gemma Marie [Del Duca], we became friends,” Thibodeaux, now 84, said. “We’re friends today. … She wants me to go to Israel with her. Can you imagine?”

The start of a spiritual bond

In 1921, the Sisters of the Holy Family were in a bind: They were primarily teachers, and the state of Louisiana had begun requiring certification. But the sisters couldn’t take the classes required for certification because schools were segregated, and Blacks were not allowed.

A call for help went out to women religious in the North, and the Sisters of Charity responded, sending six sisters from Seton Hill to New Orleans to teach summer classes. The Sisters of Charity’s own college had been granted its charter as a four-year institution only three years earlier, but the sisters designed a curriculum and got to work. Four summers later, 10 Holy Family sisters passed the Louisiana state teachers exam and were certified.

“The [Seton Hill] sisters had not been in existence that long when they responded to the call,” Thibodeaux said. “How generous they were to have done that. … They didn’t think about it. They immediately responded to a need, and at great risk because of the violence and racism that existed in our region.”

Then the state began requiring college courses for certification, and the Sisters of the Holy Family faced the same problem, as they were barred from colleges in the South. Eventually, the sisters were able to enroll at Xavier University in New Orleans, and the Seton Hill sisters changed their summer classes to college-prep courses to prepare the sisters for their university careers.

That partnership, where white sisters from the North went south to help their Black counterparts, continued for more than 30 years, until civil rights laws allowed the Sisters of the Holy Family to open their own junior college in 1957.

“Our interest in your beloved Community will never change,” Sisters of Charity Mother Claudia Glenn wrote to Holy Family Mother Mary Philip Goodman as that phase of their partnership ended, according to Celebration, the Seton Hill magazine.

Goodman replied, “We know this mutual relationship will not be severed.”

One reason it has remained intact is the relationship has never been one-way. In 1942, to mark the Sisters of the Holy Family’s 100th anniversary, Glenn established a pair of scholarships for Holy Family sisters to attend Seton Hill, a program that continued until 1976. The first Black woman to graduate from Seton Hill was a Sister of the Holy Family.

Thibodeaux was a scholarship recipient, graduating from Seton Hill in 1967. One of her English teachers there had been in that first group of six Sisters of Charity to go to New Orleans.

“They were women of great courage and generosity,” she said.

In the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the two communities conspired to bring integration to their schools and established a faculty exchange program, trading teachers so Black sisters would teach white students in the North and white sisters would teach Black students in the South. The program, which ran from 1967 to 1979, let the teachers experience life in a culture other than their own and gave the schools much-needed diversity.

The personal and spiritual relationship remains strong today.

Del Duca, 88, said the reason is as simple as it is profound: “I think we like each other.”

Though Del Duca and Thibodeaux don’t get to see each other often, and each says they should probably stay in touch more, the bond remains.

“There’s a love for one another,” Del Duca said. “When we sit down together, we can pick up immediately on the issues of social justice. I think that’s created a strong bond between us. We trust each other, that whatever cause or issue is out there, we can help each other find some insight. I think it creates a strong spiritual bond between us.”

To continue reading and see more photographs, click here.

Source: Global Sisters Report

0 Comments