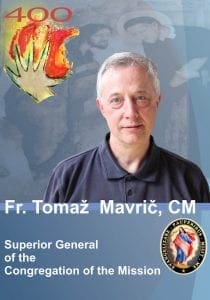

“Vincent de Paul: A Mystic of Charity”: this is the theme that Fr. Tomaž Mavrič, CM, proposes for next September 27, feast of St. Vincent de Paul, in a letter addressed to all the Vincentian Family.

After the text you will find links to download this letter in several languages.

Rome, 19 September 2016

Dear members of the Vincentian Family,

May the grace and peace of Jesus be always with us!

It is with great joy and thankfulness to each of you, who are serving “our lords and masters” all around the world, that I address this letter to you for the first time as Superior General. I would like to express my deep gratitude and admiration to all of you living and serving even in the farthest corners of the globe as witnesses to Jesus’ love! We are all servants and it is wonderful to know that in this service we are never alone. It is Jesus, our Mother Mary, Saint Vincent de Paul, Saint Louise de Marillac, and all the other blessed and saints of the Vincentian Family who accompany us on the journey.

It is with great joy and thankfulness to each of you, who are serving “our lords and masters” all around the world, that I address this letter to you for the first time as Superior General. I would like to express my deep gratitude and admiration to all of you living and serving even in the farthest corners of the globe as witnesses to Jesus’ love! We are all servants and it is wonderful to know that in this service we are never alone. It is Jesus, our Mother Mary, Saint Vincent de Paul, Saint Louise de Marillac, and all the other blessed and saints of the Vincentian Family who accompany us on the journey.

Let me take this moment to thank profoundly Father Gregory Gay, CM, our Superior General for the last 12 years, as well as all the other members and leaders of the Vincentian Family on the international, national, and local levels, who have so tirelessly and with so much enthusiasm and dedication served in the past years to make possible the affective and effective proclamation of the Good News to the Poor.

I also would like to use this opportunity to thank so very much all of you, members of the different branches of the Vincentian Family, who had written to me after my election as Superior General and expressed so wholeheartedly your good wishes and, in a special way, your promise of regular prayer. As it will not be possible for me to respond and thank each one of you individually, be assured that you are included personally in these words of thankfulness, as I extend to each of you my promise of daily remembrance in prayer.

It is a moment of “special grace” that Providence is offering us in the upcoming 400th Anniversary (1617-2017) of our common Vincentian Spirituality and Charism. Many of you already have begun intensive planning to share and encourage others to follow our Vincentian spirituality and charism on the local, national, and international levels. I encourage all of us to keep reflecting, planning, and acting together as how best to share with others this “special moment of grace.”

The motto of the whole Vincentian Family for 2017 that is going to shed light on it all is: “… I was a stranger and you welcomed me…” (Matthew 25:35). As our sight is directed toward our brothers and sisters, especially the most abandoned and those for whom no one cares, in order to be sure that our reflecting, planning, and acting go in the right direction, the path always needs to begin with us. The Feast of Saint Vincent de Paul gives us a renewed opportunity to reflect on the reasons and ways of Vincent’s reflecting, planning, and acting.

The theologian Karl Rahner, at the end of the 20th century, had pronounced these prophetic words: “The Christians of the 21st century are going to be mystics, or they will not be.” Why can we call Saint Vincent de Paul a “Mystic of Charity”?

I would like to invite and encourage each of us, individually and as a group, to reflect, plan, and act on the following point:

Why and how can I describe Vincent as a Mystic of Charity?

I asked three of our confreres, who had reflected and written on this subject in the past, to share a short personal reflection. May these thoughts help us to renew and deepen our own reflections.

1. Father Hugh O’Donnell, CM

We all know Vincent was a man of action, so we may be surprised to hear him also referred to as a mystic. But in fact it was his mystical experience of the Trinity and in particular the Incarnation that was the font of all his actions in favor of poor people. Henri Brémond, the distinguished historian of French spirituality, was the first to bring it to our attention. He said, “…it is (Vincent’s) mysticism which gave us the greatest of the men of action.” André Dodin and José María Ibañez later called Vincent a “mystic of action” and Giuseppe Toscani, CM, united mysticism and action and came to the heart of the matter in calling him “a mystic of Charity.” Vincent lived in a century of mystics, but he stood out as the Mystic of Charity.

Being a mystic implies experience, the experience of Mystery. For Vincent it meant a deep experience of the Mystery of God’s Love. We know that the Mysteries of the Trinity and the Incarnation were at the heart of his life. The experience of the Trinity’s inclusive love of the world and the Incarnate Word’s unconditional embrace of every human person shaped, conditioned, and fired his love of the world and everyone in it, in particular, sisters and brothers in need. He looked upon the world with the eyes of Abba and Jesus and embraced everyone with the unconditional love, warmth and energy of the Holy Spirit.

Vincent’s mysticism was the source of his apostolic action. The Mystery of God’s love and the Mystery of the Poor were the two poles of Vincent’s dynamic love. But Vincent’s Way had a third dimension, which was how he regarded time. Time was the medium through which the Providence of God made itself known to him. He acted according to God’s time, not his own. “Do the good that presents itself to be done,” he advised. “Do not tread on the heels of Providence.”

Another aspect of time for Vincent was the presence of God here and now – “God is here!” (influence of Ruysbroek). God is here in time. God is here in persons, in events, in circumstances, in poor people. God speaks to us now in and through them. Vincent was a man of unfolding history in the deepest sense. He followed the lead of Providence step by step. He had neither an ego-agenda nor an ideology. It took him decades to arrive at such interior freedom, which is why Vincent’s journey to holiness and freedom (1600-1625) is the key to understanding the daily dynamic of the Apostle of Charity.

2. Father Robert Maloney, CM

When we speak of mystics, we usually think of people who have extraordinary religious experiences. Their quest for God moves from active search to passive presence. They pray, as Saint Paul says to the church in Rome (8:26), “with sighs and groans too deep for human words.” Mystics have ecstatic moments when they are completely lost in God, “whether in the body or out of the body, I do not know,” as Saint Paul recounts his experience in 2 Corinthians 12:3. At times, they have visions and receive private revelations. They attempt, with difficulty, to describe for others their moments of intense light and painful darkness. Saint Vincent knew the writings of mystics like Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross. Though generally cautious about unusual spiritual phenomena, he admired Madame Acarie, one of the renowned mystics of his day, who lived in Paris during his early years there.

Vincent’s brand of mysticism was strikingly different. He found God in the people and events around him. His “visions” were deeply Christological. He saw Christ in the face of the poor. To use a phrase from the Jesuit tradition that has become popular in Vincentian documents, he was a “contemplative in action.” Christ led him to the poor and the poor led him to Christ. When he spoke of the poor and when he spoke of Christ, his words were often ecstatic. He told his priests and brothers: “If we ask Our Lord, ‘What did you come to do on earth?’ he answers, ‘To assist the poor.’ ‘Anything else?’ ‘To assist the poor.’ So, are we not very fortunate to belong to the Mission for the same purpose that caused God to become man? And if someone were to question a Missioner, wouldn’t it be a great honor for him to be able to say with Our Lord, ‘He sent me to preach the good news to the poor’” (CCD:XI:98). When he spoke about Christ, he could be rapturous. In 1655, he cried out, “Let us ask God to give the Company this spirit, this heart, this heart that causes us to go everywhere, this heart of the Son of God, the heart of Our Lord, the heart of Our Lord, the heart of Our Lord, that disposes us to go as He went … He sends us, like the apostles, to bring fire everywhere, to bring this divine fire, this fire of love …” (CCD:XI:264).

For Vincent, the horizontal and the vertical dimensions of spirituality were both indispensable. He saw love of Christ and love of the poor as inseparable. Again and again, he urged his followers not just to act but also to pray, and not just to pray but also to act. He heard an objection from his followers: “But there are so many things to do, so many house duties, so many ministries in town and country; there’s work everywhere; must we, then, leave all that to think only of God?” And he responded forcefully: “No, but we have to sanctify those activities by seeking God in them, and do them in order to find Him in them rather than to see that they get done. Our Lord wills that we seek above all His glory, His kingdom, and His justice, and, to do this, we make our primary concern the interior life, faith, trust, love, our spiritual exercises, meditation, shame, humiliations, our work and troubles, in the sight of God our Sovereign Lord. Once we’re grounded in seeking God’s glory in this way, we can be assured that the rest will follow” (CCD:XII:111).

In a ground-breaking 11-volume work written almost a century ago, Henri Brémond described Saint Vincent’s era as the time of “The Mystical Conquest.” At the conclusion of an eloquent chapter about Vincent, he stated: “It was mysticism that gave us the greatest of our men of works” (Histoire littéraire du sentiment religieux en France, III « La Conquête Mystique » (Paris, 1921), p. 257).

3. Father Thomas McKenna, CM

For this title to serve well, the word “mystic” has to be understood in its most general sense. The more popular connotation is that of a person who has more or less “direct” experience of God (visions, voices, leanings, sounds), more unmediated than not. The literature of mysticism describes experiences like ecstasies, being taken up into “a third heaven,” taken out of oneself and “sinking into” the Mystery (e.g., into the Abyss, Ocean, Ground) who is God. Its vocabulary is distinctive; e.g., progressively deeper inner mansions, active and passive contemplation, purgative/illuminative/unitive stages, passing beyond oneself, dark nights and dazzling darkness. By contrast, Vincent’s language for religious experience was quite simple and direct, and neither did he testify to these kinds of occurrences in his own life.

But the word mystic can be applied in a wider sense. That is to say, it might refer to someone who has a lived and felt contact with the sacred in life, and who responds to that encounter in service to the neighbor. Under this broader meaning, Vincent can be thought of as a mystic.

The more inclusive sense might be something like this. A mystic is one who listens to and gets caught up into God’s love for creation, and who then commits himself both to recognizing that love in the world and also bringing it there. For Vincent, this love (better, “loving”) of God revealed itself especially in people who were poor and marginalized. He came to recognize them both as privileged bearers of God’s love and as particularly deserving recipients of it. And he followed up on this by actively bringing the Good News of that love to those poor ones.

Much like the way the right lyrics can draw out the deeper beauty of a melody, the words from Isaiah that Jesus spoke in Luke chapter 4 gave a particularly resonant expression to Vincent’s experience of God. Here was Jesus announcing not only His own mission from His Father, but also His own experience of His Abba as Love for the world, especially for the downcast: “I have been sent to bring the Good News to the poor.” To paraphrase, “The fire of my Father’s love (“loving”) is burning within me, and it drives me to bring just that love to the world, most especially to the poor ones in it.” To follow the analogy, Vincent recognized these words as the lyrics to a melody that had been playing deeper and deeper within him. It was as if on hearing this text at a particular juncture in his life, Vincent said something like “Aha! That’s it! Those words catch just how I’m experiencing God’s love – and just how I want to spend my life in responding and spreading it.”

Another angle. You might describe Vincent as a “bi-spectacled” mystic. That is to say, he was (seeing) experiencing the same God through two different lenses, both at much the same time. One lens was his own prayer; the other was the person who was poor as well as the world he or she lived in. Each angle of view influenced the other, the one deepening and sharpening the perception of its opposite. Vincent “saw” (and felt) God’s love through both these perspectives at the same time and acted vigorously to respond to what he was seeing.

To keep our reflecting, planning, and acting in the right direction as members of the Vincentian Family, to help us reflect on Vincent as a Mystic of Charity, the many Congregations that are part of the Vincentian Family or will become part in the future have their own Constitutions as the first and most important source, and all the branches as a whole have the writings and conferences of Saint Vincent de Paul, as well as the writings and conferences of other blessed and saints of the Vincentian Family. May the reading and praying of these texts be part of our daily commitments.

As we approach the Feast of Saint Vincent de Paul that we will celebrate with the whole Vincentian Family, as well as with many other people, groups, and organizations whom we touch and serve, may we be deeply encouraged by this “moment of special grace” that Providence is putting in front of us, the birth 400 years ago of our common spirituality and charism.

I wish each of us a wonderful celebration, as we continue our prayers for one another!

Your brother in Saint Vincent,

Tomaž Mavrič, CM Superior General

0 Comments