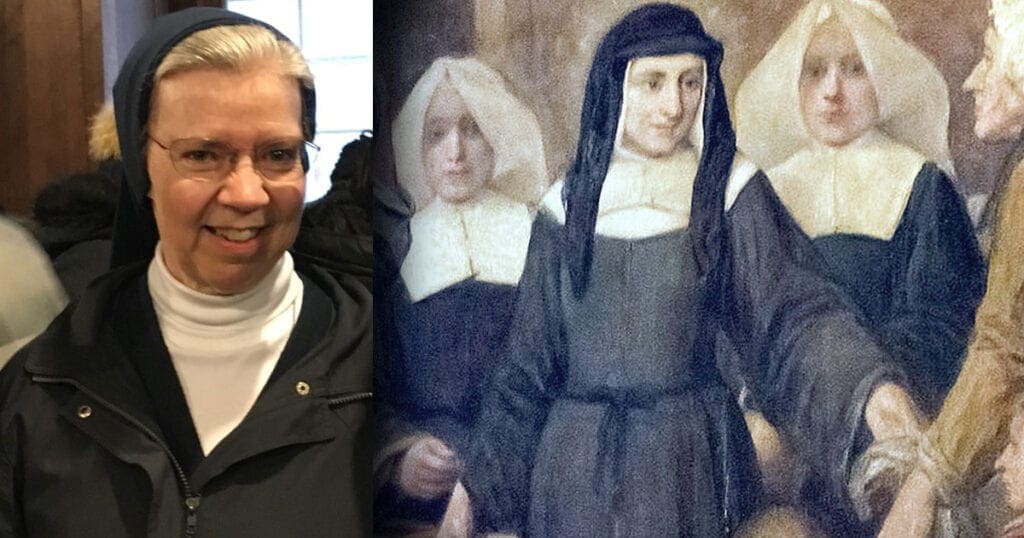

Hailed as a “first-of-its-kind” move, the announcement in early July by Pope Francis that women would become full members of the Vatican’s office that oversees religious orders was greeted enthusiastically around the world. As a staff member at DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois, where we follow in the legacy of St. Vincent de Paul, I was particularly thrilled to read that one of those women is Sr. Kathleen Appler, superioress of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul (Fr. Tomaz Mavric is “president” of the whole Vincentian family).

Thirty-five years ago when I joined my congregation, the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (or BVMs), I learned that the congregation had once been one of the largest in the United States, numbering around 2,500 sisters at its peak. I thought that impressive. That is, until I came to work at DePaul University and started to learn about the Daughters, a congregation founded by St. Vincent de Paul and his companion in ministry St. Louise de Marillac in Paris, France, on Nov. 29, 1633. The congregation quickly went international, and at its largest, prior to the Second Vatican Council, had about 45,000 members, networked in a single organization that spanned the globe. As someone who teaches leadership and organizational skills, that figure still takes my breath away,

Though that peak number has declined significantly, as with most women’s congregations based in developed countries, the Daughters still number more than 14,000 serving in 94 countries around the world.

As I have studied her, it seems to me much of that growth is due to St. Louise’s leadership and organizational skills – a story that, as with most women religious leaders, often has gone untold in Catholic history. In reality, Louise and other women founders like her were among the first “social entrepreneurs” (a popular idea these days) with not only a local, but a global vision.

Louise’s main intent was to have the sisters serve the poor and sick. However, being a good manager as well as an inspiring leader, she also wanted those women to report to her on what they encountered in their home visits. Being a child of aristocracy and herself well educated by Dominican sisters, Louise took on those young women’s illiteracy by founding her own schools.

It is worth noting, too, that this all took place counter to societal norms of the time. In particular, women who wanted to follow the calling of their faith to serve God and others were required to do so in a cloistered convent, not by walking the streets to visit the homes of the poor and sick, or running schools. Vincent and Louise countered that convention, and even got around Rome’s dictates of the time by the way they structured the order.

St. Vincent de Paul wrote: “The Daughters of Charity have… for a convent, the houses of the sick; for cell, a rented room; for chapel, the parish church; for cloister, the streets of the city; for enclosure, obedience; for grille, the fear of God; and for veil, holy modesty.”

Louise initially did not know how to run a school, so she sought advice and methods from the Ursuline sisters, a congregation of women religious founded in Italy in 1535 by St. Angela Merici, and understood to be the church’s first women’s institute dedicated exclusively to girls’ education.

That is the truly impressive thing about Catholic sisters. For centuries, when they saw a social need they wanted to address, they put time and effort into learning how to do it. A sister friend of mine, who has been a missionary in Kenya for about 17 years, once said to me, “Throughout the history of Catholic sisters, we learned how to do what needed to be done. We didn’t know how to run hospitals or clinics. We didn’t know how to run schools or colleges. We learned how to do it!”

By 1660, the year both St. Louise and St. Vincent died, the Daughters had spread from Paris to 60 convents throughout France. As reported on Grace-Inc.org, by the 19th century, the Daughters were in Austria, Australia, Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, Turkey, Britain and the Americas, running schools, hospitals, clinics, and orphanages. Today, the Daughters also educate girls who live in many poor, rural locations, including Bolivia and Brazil in South America, and Burkina Faso, Kenya, and Burundi on the African continent.

Pope Francis also appointed a consecrated laywoman to the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life. I have always been interested in the fact that prior to the founding of the Daughters, St. Vincent organized wealthy laywomen in rural villages into what were known as “confraternities.” He later put Louise in charge of visiting and managing these associations, which were to provide from their own financial means for the sick and elderly of their villages.

Visiting these rural locales, Louise again saw the need for education. She encouraged anyone in a village who could read and write to become teachers. In the Rule that was written for the members of a confraternity, it states: “They shall teach the little girls of the villages while they are there. They shall strive to train local girls to replace them at this task during their absence. They shall do all this for the love of God and without any remuneration.” Once the Daughters were founded, when Louise sent two sisters to a village to serve, she always made sure one of them was able to read and could teach young children.

To be sure, the Daughters have not been without their challenges and detractors. Bad management and excessive zeal make a mess of things anywhere. Yet, stories like that of St. Louise de Marillac abound in the almost 2,000-year history of the Catholic sisterhood. The male members of the Vatican congregation will no doubt learn a lot from the courageous, pioneering women with whom they will now serve.

Source: Global Sisters Report

Patricia M. Bombard is a member of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Dubuque, Iowa. She has a doctorate of ministry, has worked in various capacities in the areas of business, politics, journalism and higher education administration, and taught at St. Xavier and Loyola Universities in Chicago. She is currently directing DePaul University’s Vincent on Leadership: The Hay Project.

0 Comments