(With information from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime)

Many Catholic organizations and parishes are engaged in the effort to end human trafficking through supporting victims, sanctuaries, and legislation related to the atrocity. But how much do we know about human smuggling?

Recently, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) issued its first Global Study on Smuggling of Migrants, which offers insight into the crime.

DEFINITIONS

It’s important to understand the differences between human smuggling and trafficking in persons. They are two separate crimes, although they can often overlap. Both often involve poor, desperate, and vulnerable people. One relates to arrangement of transportation while the other is about exploitation.

Human smuggling, also called migrant smuggling, occurs when someone pays or provides other material benefit to another to gain illegal entry into a country of which that person is not a national or resident. When someone’s life is in danger or they are living in poverty, such payments can often compound their desperation.

Trafficking in persons involves recruiting, transporting, transferring, harboring or receiving persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability, or giving or receiving payments or benefits, to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Trafficking in persons reduces people to “human commodities” who are manipulated, abused, and ill-treated.

DISTINCTIONS

Migrant smuggling can be intertwined with human trafficking. But there are distinctions. Migrant smuggling is typically voluntary and involves the person being taken to another nation. Profits come from arrangement of the transportation. Exploitation stops when the person arrives at their destination. With human trafficking, the victim either has not consented or has withdrawn consent. Further, human trafficking is not necessarily transnational. It can occur within a country. And profits come from exploitation of the victim.

The lines between smuggling and trafficking often begin to blur. For example, a migrant may pay a smuggler for transportation but wind up in forced labor.

UNODC STUDY

The recent UNODC Global Study on Smuggling of Migrants was issued on June 13, 2018. According to that report, almost 2.5 million persons were smuggled in 2016, generating up to $7 billion US dollars, which is equal to the amount the United States or the European Union spent on humanitarian aid that year. Sobering, indeed, when one thinks of how much a person must sacrifice to raise funds necessary to seek a more promising life or escape violence, and the perils faced during the journey.

SMUGGLING ROUTES

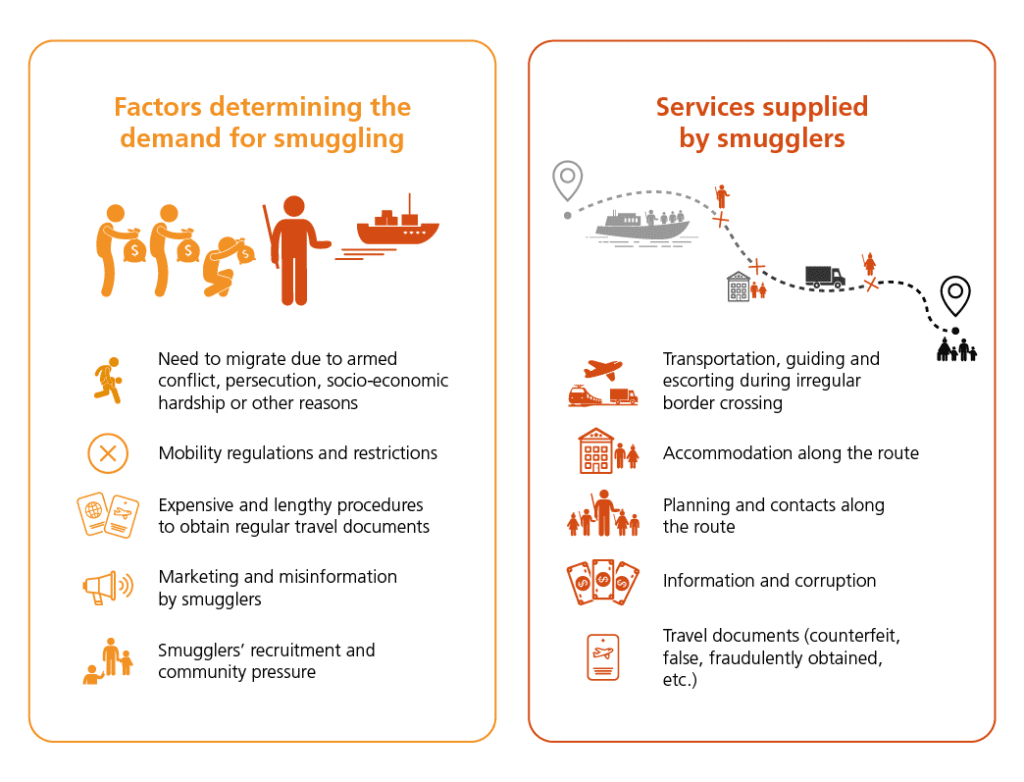

Migrant smuggling affects almost every country in the world, according to the UNODC report. There are about 30 major smuggling routes in the world, it indicates, noting that the demand for smuggling services is particularly high among refugees, who may need to use people smugglers to reach a safe destination.

CORRUPTION

It is not surprising that smuggling networks can involve systematic corruption, from local to international levels. The UNODC mentions various schemes, from fake marriages or employment rackets, to counterfeiting travel documents and the corruption of senior officials.

Smuggled migrants and their smugglers can remain for long periods of time in transit countries, often under conditions of extreme hardship. Smugglers may recruit among local or migrant communities, spreading the criminal impact of their business along their routes, the UNODC states.

PROTOCOL AGAINST SMUGGLING OF MIGRANTS

Internationally, human smuggling is addressed in the Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, also called the “Migrant Smuggling Protocol.” It supplements the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, which took effect on January 28, 2004. The protocol has three purposes:

- To prevent and combat the smuggling of migrants

- To promote cooperation among States Parties to that end

- To protect the rights of smuggled migrants

PERILS

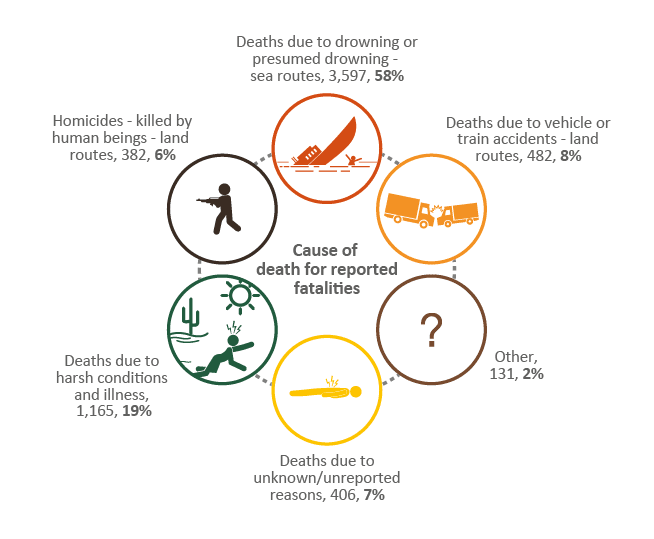

Every year, thousands of migrants die during smuggling activities, according to the report. In 2017, there were 3,597 deaths due to drowning or presumed drowning; 482 due to vehicle or train accidents; 1,165 due to harsh conditions and illness; 382 homicides on land routes; 406 due to unknown or unreported reasons; and 131 other deaths.

Accidents, extreme terrain and weather conditions, as well as deliberate killings have been reported along most smuggling routes. Many migrant deaths go unreported, along unmonitored sea routes as well as remote or inhospitable stretches of overland routes. In addition to fatalities, smuggled migrants are also vulnerable to a range of other crimes, such as violence, rape, theft, kidnapping, extortion and trafficking in persons. Such violations have been reported along all the smuggling routes considered in the report.

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE POLICIES

A holistic approach to countering the smuggling of migrants needs to consider not only where it happens, but also contributing factors, the report indicates. Since migrant smuggling is related to a mix of demand and supply elements, it requires a comprehensive strategy which takes into consideration complex factors.

Some means of addressing migrant smuggling could include:

- Reducing demand by broadening options for regular migration and increasing accessibility of regular travel documents and procedures

- Awareness raising about the dangers involved in smuggling

- Providing alternative livelihood programs

- Improving regional and international cooperation and national criminal justice responses

- Creating financial sanctions (for example, the ability to confiscate proceeds from people smuggling)

- Because migrants and refugees are often interconnected in origin and destination countries, and sometimes en route, engaging with telecommunications and social media entities could support migrants in gaining access to information related to first aid, risks along their route, ruthless smugglers and other potentially life-saving information.

- Creating and enforcing anti-corruption mechanisms

- Collecting and analyzing data, and engaging in research at all levels (which would support policy making)

Margaret, thank you for bringing this study to our attention. Many of the refugees I work with were smuggled and I look forward to reading it, especially the European context. Breege, D.C.