A few years ago, my sister-in-law told me about the changes in the classroom of my nephews, their activities and all those little things that helps children learn to socialize. Thus, among other stories, she told me this of my little niece, 5 years old then, facing the dilemma of choosing a “boyfriend” between two of her classmates. She thought to give them points for every good thing they did, and— of course— that one getting most points would finally be her official boyfriend. But, days later, my niece stopped giving points to her applicants. When my sister-in-law asked why she was not giving more than twenty points, she replied, “that is because I have reached the top… I have not yet learned to count beyond.” Another thing she told me about my niece was the terror that she felt on Halloween: she was convinced that during this evening, she would become a werewolf and kill her parents.

Leaving aside the wonderful fantasy of children’s minds, I would like, with this anecdote, to reflect briefly on Halloween, so popular in our present times.

Halloween is a feast of Celtic origin that was brought, especially in North American culture, by Irish immigrants, about 150 years ago. The word Halloween comes from the expression All Hallow’s Eve.

Tradition, especially in Anglo-Saxon countries, is: after knocking the door, children say the sentence “trick or treat.” If adults give them candy, money or any other reward, it is interpreted to have accepted the deal. Instead, if they refuse, the children make them a little joke, like throwing eggs or shaving foam against the door. Originally, “Trick or Treat was a popular legend of Celtic origin, according to which not only the spirits of the dead were free to roam the Earth at Halloween night, but all kinds of entities from all spiritual realms. Among them, there was one, specially malevolent, wandering through towns and villages, going from house to house asking, precisely, ‘trick or treat.’ The legend says that it was best to treat, regardless of the cost it had, as not agreeing with this spirit (whose name was Jack O’Lantern) he would use his powers to ‘trick,’ which would be to curse the house and its inhabitants, giving them all sorts of misfortunes and curses such as becoming sick, killing the livestock with pests, or burning the house itself.”

There is no doubt of the commercial background of this holiday, and the influence of horror movies where Halloween has appeared with some regularity, to increase its popularity.

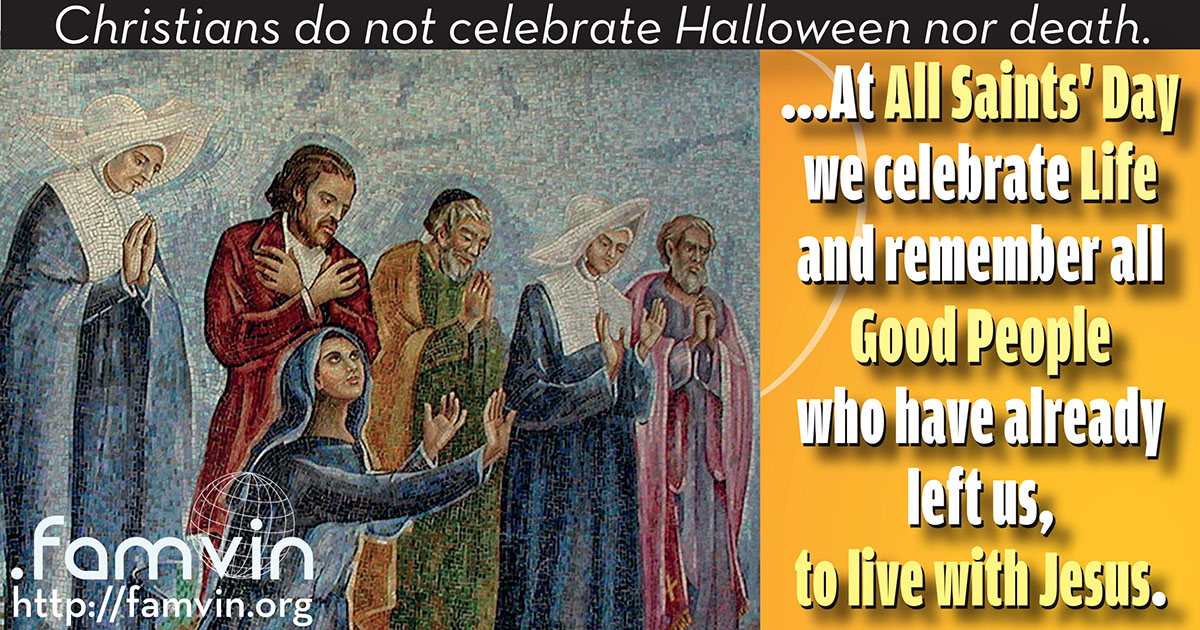

Christians do not celebrate the death and darkness of Halloween. Christians celebrate, on November 1, the Feast of All Saints, in which we remember and pray for all those who came before us and gave their lives to improve ours. The custom brings us, during this day, to cemeteries, to visit our loved ones who have already departed to the Father’s house, showing them our love and respect, and praying for them and for us. It is a custom that, although it seems not to, celebrates life: the life lived among us and the life they are enjoying next to God the Father.

On this feast we also remember all those holy and faithful followers of Jesus Christ, even those the Church has not officially canonized. Many are, certainly, the good people who have given and give their lives to build the Kingdom of God. In this thanksgiving to God for all of them, we also ask the Lord to make us like them.

In social networks we see many posts on this issue. From party ads to have fun on Halloween night, to proclamations against Halloween and its pagan liturgy. We know that many unbelievers— and also some believers— will go out on Halloween night with their costumes, their “tricks and treats,” both children and adults… although Halloween influence varies, like so many other things, between countries and cultures; in the United States is deeply rooted; in Europe its influence depends on each country; elsewhere …

I think this is a good opportunity to sit down with our children and teach them to look at these days with a believer look, perhaps using the occasion of a recent loss of a relative or a friend they knew. To tell them, for example: “that person was so good, so good, that Jesus wanted him/her to go to live with Him, as He wants us in the future.” It is important to adapt the content to your child’s eyes, so that they may understand what is the truth behind the feast; and also explain them that Halloween, a day that most likely they will not be able to avoid in their schools or in society, is nothing more than a game, a “costume party;” to make them know, ultimately, that costumes, pumpkins and Halloween candy are in the area of the unreal fantasy, while they may know that the next day we will hold something else, very different and very beautiful: the joy of still having good friends and relatives most loved by our daddy God, although we may not see them anymore.

This post began with an anecdote that might seem to have nothing to do with the subject: that of my niece, 5 years old, but could not count beyond 20. But, if you think about it, this All Saints’ Day is a good opportunity to teach our children to count “beyond” —metaphorically speaking—, and not simply to remain “counting” the first numbers (=appearances, the external, the superfluous, the superficial, the accessory). Let’s teach our children to count the “large numbers” of this story: goodness, holiness, family, friendship even in the distance, … the great love and mercy of a Father who awaits us!

Javier F. Chento

![]() @javierchento

@javierchento

![]() JavierChento

JavierChento

0 Comments