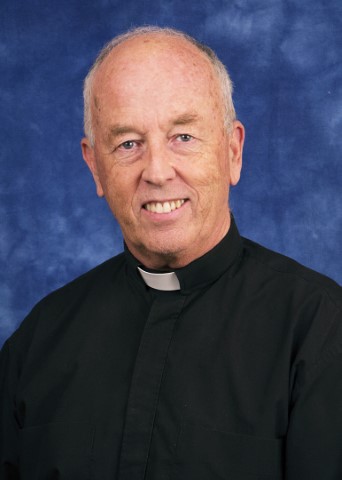

In his reflection titled Someone Who Knows, Fr. Tom McKenna, reflects on Downton Abbey’s ‘upstairs-downstairs’ structure and someone who knows both sides.

In his reflection titled Someone Who Knows, Fr. Tom McKenna, reflects on Downton Abbey’s ‘upstairs-downstairs’ structure and someone who knows both sides.

(Hebrews 4: 14-16; Mark 10:35-45)

In the letter to the Hebrews, and then again in Mark, we come across two tables. For Hebrews it’s the Kingdom table, the heavenly banquet one, set around the Heavenly Throne on which Jesus sits. In Mark, there’s the earthly table in Palestine, the one which Jesus is asking his disciples to serve at. But there’s something else about those tables the readings make reference to, the different spaces around them, more precisely the different social spaces surrounding them. There are the places around the table where people sit and dine; there are the places below that table, outside that circle, where people stand and attend to the diners. There are the people who feast and those who serve the feasters, the higher and lower levels.

So in Hebrews: Jesus, the enthroned High Priest both sitting at the head of the table, but also going down from the throne to the lower level, down into creation in all its aspects, taking on our condition with its joys and limits, limits even unto death. Jesus takes both positions around that table and is portrayed as the access channel between them both.

In Mark: Jesus telling James and John that the ability to sit at the highest places (the glory places) at the table will come only by working along with the waiters and waitresses and bus boys and maids serving at the lowest places. You have to stand below if you’re ever going to sit up high.

This idea of the two-tiered table conjured up, of all things, some episodes and scenes from the hit PBS series, Downton Abbey. The whole show, as its fans would know, is built around the contrast between the aristocrats and the commoners, the upstairs and the downstairs. And nowhere is this difference more evident than at the nightly dinner table – those sitting and those standing, those partaking and those serving. Upstairs, the deference paid, attention given, the absence of easy conversation between the sectors, the formality of it all – as contrasted with the informality of downstairs, the eating habits, the quality of their food and drink and tableware, all the banter and familiarity. The boundaries in that house, and especially around that table, are clear and firm. The whole set is staged to hit you with the social distance between the two.

But then the boundary line gets crossed, and a whole different dynamic begins. Someone from the upper table, the Lord’s daughter, and someone from the lower one, Tom the chauffeur, fall in love – and marry. And so commence many episodes of high drama about how this crossover plays out – all the gaffes and strains and resentments and adjustments and reconciliations and even acceptances that get stirred up along the way.

Let me focus on one of the recurring themes.

The servers feel good about one of their own now being up there, now being served. They’re deferential to him, but in a knowing, winking way. “We’ve got one of us sitting at the high table. If there any problems come up, he’s in a position to help us. Not only that, he’s someone we can talk to and in our own language, someone we can approach.”

And then there’s Tom the chauffeur, the one who moved up. Unlike anybody else at that main table, he genuinely understands the servants. And that’s because he’s been one of them himself. His personal experience gives him an entrance into their skin. He can empathize, sympathize, see the world through their eyes, and again in a way the others just can’t. And you can feel it in the kinds of exchanges that go on — sometimes bumpy, sometimes tender but always on much the same wave length.

And so we see him acting as a kind of go-between, standing on both sides of the aisle. There are times when he’s explaining, even defending, the downstairs to the upstairs. There are others when he’s down in the kitchen explaining, even defending, the lords and ladies upstairs to the paid employees.

His ability to do this interceding and reconciling is grounded not just on his being a nice guy, not even on his credential of having been at both levels in that dining room, but on the more basic fact that somehow he’s gotten in touch with the reality that everybody in that house, fundamentally, is on the same plane. There’s a basic equality at the banquet he now knows about. His two “locations” at the table enable him to know that those distinctions so played up by dress and education and accent are not near the heart of it all. Moving between social zones, he’s able to connect one with the other and look with sympathy on both.

We go back to Jesus and the two disciples who want to get their bids in early, be the first on the inside track. Jesus says, “You want to sit with me at the head table in glory, do you? To get there, you’re going to have to serve at that table, to put the needs and desires of the people sitting there ahead of your own. The only way to be at my head table is to learn how to serve from that lower table. That’s what will give you that hard to come by sense that all of us are servants and at the same time masters – all equal in the eyes of my Father and each uniquely loved by my Father.

[An interesting aside: Jesus is saying to himself “if they only knew what they were getting into.” Because in fact the two people who do come to be at his left and his right in glory turn out to be the two thieves hanging on their crosses next to his. Once again, the way to the upstairs table is the downstairs way of the servant who suffers.]

The Downton Abbey scenario is one way to look at Jesus the High Priest who “knows our condition,” and who therefore is approachable, and from whom, as Hebrews says, we can ask and expect “timely help.” He’s somebody sitting at the high table who knows the low table. He’s someone enthroned who knows what it’s like to be living underneath the throne. He’s someone who knows both languages, His Father’s and ours – and so can reconcile. He’s someone to go to, who is able to take both sides.

There are connections here to our Vincentian spirit. One is with our “aspiration virtue” of humility. A good description of this is the gift to see where we stand before God and our fellow humans.

Isn’t this the gift to see that we’re both diners and servers, people who are called to sit that banquet table under the loving gaze of the host, and at the same time asked to stand around it and serve the others. Forever sitting at the head table and never being a server at it can bring on the delusion that it’s really not Christ the Lord sitting at the head of it but myself! Too much standing on the outside of the circle with no sense of inclusion in it can lead to underestimating the regard in which we’re held at that table. Humility is the balance between the diner and the server.

And when you press the point, all those other St. Vincent virtues can cluster here too:

- simplicity – being who you are whether up on the dais or back in the kitchen;

- meekness – being approachable;

- zeal – service, given from the heart;

- mortification – moving off the seat at the table when service at it is more needed;

- charity – service given from a heart on fire for the coming of the Kingdom where all sit as equals before the loving gaze of the host.

Two places around the table, each one an honored and necessary place at the Kingdom banquet.

0 Comments