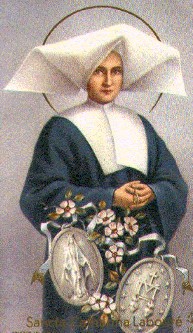

Catherine Labouré was born in Fain-les-Moutiers (France) on May 2, 1806 and entered the Company of the Daughters of Charity on April 21, 1830. Although favored with the apparition of the Blessed Virgin and other supernatural graces, she led an obscure life of dedication to the needy. She died on December 31, 1876. She was beatified on May 28, 1933 and canonized on July 27, 1947.

Youth

Pierre Labouré, a former seminarian who “preserved through the bad days the Christian sentiments of his Seminary education” (“I know from my own mother that her parents were very Christian. Her father had spent some time in the Seminary before the Revolution, and had preserved, through the bad days of that time, the very Christian sentiments acquired in his first education,” Testimony of Mrs. Duhamel, niece of St. Catherine, in the Process of the Ordinary, November 24, 1857). He married Louise Madeleine Gontard, a teacher in the village, in Senailli on June 4, 1793. These were the bad days of the French Revolution. In 1800, he moved to Fain-les-Moutiers, a small village in the center of France, in the Burgundy region. There he cultivated land that belonged to him. He was a peasant of sufficient means, neither rich nor so poor.

On May 2, 1806, a daughter was born, to whom they gave the name Catherine and the nickname Zoé, because she was baptized on the feast of Saint Zoé, a word that means life. This nickname, however, does not appear in the civil registry nor in the parish register. Catherine’s parents would have a total of 17 children, of whom 10 would live. Catherine was the eighth of those who lived. She was followed by her sister Tonina and by Augusto, the youngest, a very sickly child.

Their mother died on October 9, 1815, when Catherine was nine and a half years old. An aunt of hers takes her and Tonina with her, while the third of the sisters, Maria Luisa, who is already twenty years old, takes charge of the house.

But Marie Louise entered the Daughters of Charity on June 22, 1818, and Catherine returned to her father’s house in January of the same year to take over for her sister. Catherine made her first communion on January 25, 1818.

At the age of 12, Catherine became a woman of work and responsibility. This period would inform her life with virtues that would always accompany her: work: efficiency, silence, sacrifice. She tells her sister Tonina: “Between the two of us we will make the house run”. The task is more than difficult: there were many siblings at home, in summer there were up to twelve seasonal workers, there was a farm with many animals. It was necessary to cook, wash, sew, take food to the workers, to the chickens, to the “seven or eight hundred pigeons”. This anecdote of the pigeons from the Labouré’s dovecote fluttering around Catherine always stands out. Little poetry for so much work.

On top of that, she was given to penance and prayer. At the age of fourteen she decided to fast Fridays and Saturdays. Tonina found out and told her father; the father got angry and argued with his daughter. Catherine convinced him and continued fasting. When she finished her homework she would go to the church to pray and she did it without haste and on her knees on the floor, cold and wet most of the time. She would suffer all her life from arthritis in her knees. She often prayed before the picture of the Immaculate Conception, hands outstretched and feet on the head of the snake, in the parish chapel restored by the Labouré family. There was no resident priest in the village and she had to go to Mass with her family in Moutiers St Jean, half a league from Fain.

She also went to parties in neighboring towns with friends her age. People who knew her later stated that she was blue-eyed, very cheerful and “with an experience and dedication of someone older”. A woman who had occasion to observe her when she went to the festivities of Cormorin, would say many years later, in 1887: “She was not pretty, but gentle and good. Kind and sweet to her companions, even when they tried to make her angry, as children do. And if she saw that the others were angry, she tried to make peace. If a poor person showed up, she would give him what goodies she could get. When the relatives came to the feast to go to the patronal mass, Catherine prayed like an angel in the temple and did not turn her head to the right or to the left (Sister Caseneuve, Process of the Ordinary, June 1, 1897).

Call

When Catherine was 18 years old, she had a dream: She was praying in the chapel of the Virgin, a priest went out to celebrate Mass, every time he returned to the village he looked at her with penetrating eyes; when Mass was over, the priest came out of the sacristy and called her; Catherine ran away and went to visit a sick person; the priest appeared there and told her: My daughter, it is good to take care of the sick; you run away from me now, but one day you will be happy to return to me; God has designs on you, do not forget it. Then the dream ended.

Five years went by and she hardly remembered the dream. It is September 1829 and Catherine is in Chatillon-sur-Seine, where the Daughters of Charity have a residence. Catherine goes to visit them. When she enters the hall, she notices a painting on the wall and is startled: that person, St. Vincent de Paul, is the priest from her dream.

Catherine, before she had seen the painting, told her father that she wanted to be a Daughter of Charity like her sister Maria Luisa, and her father was against it. It was enough that the eldest daughter did that. Since he knew that he would not win by arguing, he hatched a plan. Catherine was normal, cheerful, did not shy away from parties, and several boys had already asked her to marry. She would go to Paris, the stunning city. Five of Catherine’s siblings already worked there. Charles had a small restaurant for workers, 20 Echiquier Street, in the neighborhood of Notre Dame de la Bonne Nouvelle. Let’s see if there, between the kitchen and the table, between the words and the compliments, she would forget such ideas.

Catherine went, worked, and remained unwavering in her decision. She wrote to Marie Louise, the Daughter of Charity, and the latter answered her with an ardent letter: “What does it mean to be a Daughter of Charity? It is to give oneself to God without reserve in order to serve Him in the poor, in His suffering members? If at this moment someone were powerful enough to offer me the possession not of a kingdom but of the whole universe, I would look at all that as the dust of my shoes, quite sure that I would not find in the possession of the universe the happiness and contentment that I experience in my vocation”.

Marie Louise had no idea what would happen to that letter. When, for humanly explainable reasons, she had to leave the community of the Daughters of Charity, her sister, then already Sister Catherine, would return the letter to her, corrected and enlarged. And Marie Louise would rejoin the community in 1845.

Daughter of Charity

Marie-Louise, in her letter, advises Catherine to go to Chatillon-sur-Seine with a sister-in-law of hers, married to Hubert Labouré, who ran a boarding school for young girls. There Catherine learns to read and write a little, because until that moment -and at a good price: 30 francs- she had only learned to sign her name. In Chatillon, she became acquainted with the Daughters of Charity, recognized the priest of her dream in the picture in the foyer and, finally, made her postulancy, a prerequisite for entry into the Daughters of Charity. Her postulancy form, January 14, 1830, reads as follows: “Miss Labouré, sister of the one who is superior of Castelsarrazin, is 23 years old, of good devotion, good character, strong temperament, love of work and very cheerful. She receives communion regularly every day (a lot for the time). Her family is impeccable in its morals and probity, but of little fortune. She has brought 672 francs as a dowry”. Peter the farmer did not want to give her any dowry and it was his sister-in-law who provided it, although not in full.

After the postulancy came the novitiate or seminary. On April 21, 1830, Catherine arrived by horse-drawn carriage at the motherhouse and novitiate of the Daughters of Charity. It was the Wednesday before the transfer of the relics of St. Vincent de Paul from Notre-Dame to St. Lazarus, April 25, 1830.

“The body of St. Vincent had been respected during the French Revolution because of his reputation for charity, one would say rather for philanthropy. It was deposited in a crypt of the Notre Dame Cathedral. We know that the members of the Congregation founded by St. Vincent had initially settled in the priory of St. Lazarus. Hence the name Lazarists, which is still in use today. But in 1830, the Lazarists moved to 95 rue de Sevres, a few steps from rue de Bac.

On Sunday, April 25, a procession led the remains of St. Vincent from Notre Dame to the chapel in the rue de Sévres. It was a solemn procession, in which eight hundred Daughters of Charity marched. The young Catherine took part in it.

After the transfer there was a novena of prayers in the chapel on rue de Sévres, before the body of St. Vincent. Catherine attended.

The first mystical event of her life occurred in this effervescence, in this Parisian month of 1830…” (Jean Gutton, “Superstition Overcome (Rue du Bac)”, Ed. Cerne, pp. 45-46).

St. Vincent de Paul

What was this first event? The vision of St. Vincent’s heart, which Sister Catherine narrated on February 7, 1856:

“I arrived on April 21, 1830, which was the Wednesday before the transfer of the relics of St. Vincent de Paul, so happy and content to have arrived at this great feast that it seemed to me that I was not on earth. I asked St. Vincent for all the graces I needed and I also asked him for the double family [Daughters of Charity and Congregation of the Mission] and for the whole of France, for it seemed to me that it was in the greatest need. Finally, I begged St. Vincent to teach me what I should ask for with living faith; and every time I went to St. Lazarus, I felt great sorrow. It seemed to me that I found St. Vincent in the community, or at least his heart, who appeared to me every time I went to St. Lazarus.

“I had the consolation of seeing him on the little box in which the relics of St. Vincent were displayed. He appeared to me three different times during three consecutive days. Flesh-colored white, he announced peace, calm, innocence, union. Then I saw him red with fire, because he was to enlighten charity in hearts: it seemed to me that the whole community had to renew itself and extend itself to the ends of the world. Then I saw it dark red, filling me with sadness for the pain that had to be endured. I don’t know why or how this sadness focused on the change of government. However, it did not prevent me from speaking to my confessor, who calmed me as best he could, drawing me away from these thoughts…” (Laurentin René, “Catherine Labouré et la Médaille Miraculeuse”, three volumes, Paris 1976-1980, I, pp. 334-335).

During her novitiate, Catherine had visions of the Miraculous Virgin, of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament, of the Cross. Those visions, for the time being, were only her world, not yet the world of her sisters of the motherhouse nor the world of the Church. That is why no one suspected anything. Catherine did not radiate any extraordinary halo. The descriptive note that the superiors wrote about the novice Catherine Labouré is terse and anodyne: “Strong, of average size, can read and write, her character seems good, her spirit and judgment are not brilliant, she is pious, she works in virtue”.

Enguien

From the novitiate, in February 1831, she left for her first assignment: the hospice for the elderly in Enguien. Her first and only assignment. Except for a few days during the Paris Commune, she remained there until the day of her death, December 31, 1876. Almost 46 years in the same house.

Successively, and sometimes cumulatively, she was in charge of the kitchen (1831-1836), the linens (1836-1840), the cowshed (1846-1862), the henhouse (1831-1865), the care of the whole house, although without the title of superior (1860-1875), and finally the porter’s lodge (1870-1876).

As can be seen, there are no big changes in Catherine’s life story. Her balance of spirit and her stability in her work astonish the present viewer and prove the truth of her relationship with God.

Speaking of the two types of writings from her pen – on the one hand her notes and accounts, and on the other her accounts of the apparitions – Laurentin makes this comment:

“In the two aspects of her activity, she belongs to the world of the poor: those who have neither the time nor the means to learn to read and write, without lacking intelligence and ability.

Whether it is a secular writing or a message she has received from another world, Catherine shows the same order, the same consciousness, and also the same lack of spelling. She seems to have found from the beginning the form of her writing, its spaces, its margins, which do not move from her first writings to the moment when she no longer has the strength to write. The writings of 1876 resemble the others. Impossible to date them by a change in the form of the letters…

In the moral as in the spiritual, in her life as in her writing, Catherine manifests the same sharpness, the same straightness, the same cleanliness, a capacity to go to the essential without stumbling over obstacles; no literary skill, but a clarity, a continuity. She goes straight to the objective, squeezing from within what comes to her, with the forgetfulness and eclipses common to those who are not writers; but one thing is clear: she discards everything that has no meaning.

The writings of the visionary appear deeply linked to the rest by the interior: responsible for a family since she was 14 years old, Catherine felt spiritually responsible for the religious families to which she belonged, for France in whose heart she lived, for the whole Church. Her prayer, her union with God were receptive to the prophecies that enlightened her interior solicitude. Her charisms were not for her privilege but for her service. The Blessed Virgin did not appear to me, she said, but for the good of the Company and of the Church. (Laurentin René, Ibidem, p. 125).

The poor

The Daughters of Charity “are persons dedicated to God for the service of the poor,” said St. Vincent de Paul.

The poor, for Sister Catherine, were the elderly of Enghien. She loved them not only with her heart, but also with her presence and works. Consequently, they loved her, as attested by witnesses.

When those old people came home with more wine than they could handle, she would take them in and wait for the next day to scold them. If someone asked her why she was so moderate in her scolding, she would reply, “I see Jesus Christ in them.”

She was especially patient with people in distress. One Sister complained about her attentions to an obviously wicked old man and Sister Catherine replied, “Ah well, Sister, pray for him.”

During the revolution of 1871, the militiamen of the Commune occupied the house of Enghien accompanied by “soldieresses”. One of them, named Valentina and described as “monstrous” by documents of the time, ended up in court. Sister Catherine was called as a witness for the prosecution and what she did, according to Sister Cosnard, one of the Sisters of Enghien, was “to speak so well that she saved the life of the citizen…, the citizen who had made us suffer so much” (Sister Cosnard, Apostolic Process, July 9, 1909).

Catherine prayed, and provided the soup even “when the hungry Parisians did not disdain any food – donkey, cat, rat” and handed out the Miraculous Medal to all.

Before leaving Enguien those few days when all the Sisters had to do so, she went to the statue of the Virgin in the garden, so dear to her, removed the crown and took it with her. On returning from Bellainvilliers where she had taken refuge, she found the image in the garden smashed and so she placed the crown on the statue in the chapel. It was May 31, 1871.

Incognito and amnesia

These two words, unavoidable in any biography of St. Catherine, reveal, apart from the instructions she may have received from heaven, the best peasant astuteness.

Incognito means that Sister Catherine managed so that, during her whole life, only her confessors knew that she was the one favored with the visions and apparitions that we already know. The last year, 1876, her superior, Sister Juana Dufés, also knew about it, although it is probable that by then the matter was already a “family secret”.

Amnesia refers to the fact that, for a time, precisely when the “Quentin Canonical Inquiry” (1836) was opened and Sister Catherine could be called to testify, Sister Catherine forgets everything, she remembers almost nothing of what happened and it is useless to summon her for any statement.

Laurentin, benevolent with the saint, praises the incognito and explains amnesia is probable:

- (Incognito): “How to keep a secret with so many direct and indirect means to be torn out? A little weakness or complacency, as well as tension or anxiety, would have been enough for Catherine to become the prey of all the fervors surrounding the miraculous medal. Whatever the part of grace in this matter, the effective defense of Catherine passes through a control of herself without decay and a sure instinct of peasant prudence? Catherine knew how to defend her incognito, assuring the diffusion of the message received thanks to the institutions of the Church, using the secret of the internal forum to obtain publicity in the external forum. Thus she lived her daily service of charity, as a daughter of St. Vincent de Paul, with her secret garden, her communication from heaven. And thus she found the only way, for a woman of that time, to speak out effectively: through an interposed male person”.

- (Amnesia): “An eclipse of the memory is not strange in this matter (and Laurentin cites the cases of the visionaries of Pontmain and Lourdes, also of Thérèse of Lisieux)… What is strange in Catherine is not an easily explainable forgetfulness, but the contrast between this forgetfulness and the growing precision of the memories evoked until 1876, the last year of her life. What is strange in Catherine is not an easily explainable forgetfulness, but the contrast between this forgetfulness and the increasing precision of the memories evoked until 1876, the last year of her life. Should we compare Catherine to those fruit trees that have a last flowering and a last harvest after years of sterility and before dying the following year? Should we explain this phenomenon by the eclipses and fortuitous reviviscences of the human memory that lacks the mechanical rigor of a computer? Or was there in Catherine a peasant policy of amnesia? –I do not know, I do not know more…, it is the eternal answer of the people of the countryside to the curious and indiscreet…” (Laurentin, o.c., pp. 131 and 138).

The end

Not only her knees with their arthritis, but also her heart and even her head began to fail Catherine from the beginning of 1876. She was only allowed to attend to the porter’s lodge. She had been taken away from polishing the living room floorboards and cleaning the old people’s chamber pots at daybreak.

In November, she made her last retreat in the Chapel of Apparitions at the Motherhouse. When she returned to Enghien, she had to confine herself to her room until the end. On one of the last days of the month, she asked Father Chinchon to hear her confession. And so December 31 arrived.

I will no longer see tomorrow, she said.

Sister Dufés contradicts her. Fr. Chevalier comes to visit her. Her niece, daughter of her sister Tonina, also arrives with her two little girls. The sick aunt gives them all the candies and medals she has left. The Sisters of the community follow one after the other, going from the sick woman’s bedside to their occupations.

The superior tells her that she will recover. Sister Catherine repeats that she will die that same day. A Sister brings her more Miraculous Medals, but Sister Catherine can no longer hold them in her hands and they scatter on the bed.

The Christian rite of the agony begins. Catherine would have wanted 63 Children of Mary to pray, one each, the invocations of the litany of the Immaculate Conception. But the girls from the orphanage were with their families because of the New Year’s holidays. The Sisters pray them, without Catherine being able to answer, “as silent at the moment of death as she had been in life”.

At seven o’clock in the evening, sweetly, she falls asleep – this is the expression used by all the witnesses – and dies.

Anticipated devotion

The news spreads like lightning and everyone suddenly knows that the one who has died is the seer of the Miraculous Medal. The uninterrupted parade of people who want to venerate her and touch her body or her dress with a medal begins. There is no sadness, only grateful confirmation of the presence of God and Mary among men. “When one of our Sisters dies, sadness invades us. But, in the death of Sister Catherine, nobody cried, we did not feel sad, it seemed to us that we were next to a saint” (Sister Tanguy, Apostolic Process, June 9, 1909).

Sister Dufés, the superior, called the Sisters and read to them the accounts of the apparitions that Sister Catherine had written and given to her in the spring of that year. A moving spiritual reading in an unforgettable end of the year.

The burial was celebrated on January 3, feast of St. Genevieve of Paris. The procession was led by the elders of Enguien, who had been the first in Sister Catherine’s life. Then, the Daughters of Mary with their banner, many children, young workers from the suburb of St. Anthony with the medal hung on their chests by a white ribbon, people from the neighborhood and from many other places, missionaries of St. Vincent and other priests, 250 Daughters of Charity. They sang and prayed joyfully.

They took the body of the saint in her house in Enghien and, singing “O Mary conceived without sin”, they crossed the garden in procession and deposited the body in a crypt under the chapel of the neighboring house of Reuilly. Someone would later refer to that procession as a “premature worship.”

The saint

Catherine Labouré was beatified on March 25, 1933 by Pius XI and canonized by Pius XII on July 27, 1947. Her body rests today under the statue of Our Lady of the Globe in the altar of the chapel of Rue de Bac dedicated to her. The place no doubt Catherine would have chosen if she had been asked.

Catherine’s holiness was the holiness of the poor. Without glitter and without halos, with the anti-protagonism of concealment in the most humble services. The gifts of the Holy Spirit pass through the particular filter of each person and are translated in many ways for the enrichment and edification of the Church. Catherine’s way coincides with the evangelical disposition of Jesus and with the shadowy existence of Mary and Joseph. The profound communication with God, the highest mystical gifts generously nourish an existence and in the most unsuspected way fertilize many others throughout the world. But that concrete existence, that saint, that river of divine predilection and ecclesial fruitfulness, remains hidden, making its itinerary in silence and humility. Catherine Labouré was called “Violet under the grass.”

0 Comments