“Today, however, we have to realize that a true ecological approach always becomes a social approach; it must integrate questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor.”

Pope Francis – Laudato si’

“The question which is agitating the world today is a social one. It is a struggle between those who have nothing and those who have too much. It is a violent clash of opulence and poverty which is shaking the ground under our feet. Our duty as Christians is to place ourselves between these two camps to accomplish by love, what justice alone cannot do” – Blessed Frederic Ozanam

In a modern-day clash between opulence and poverty, a dialogue is needed to truly understand how the charity retail sector, the SSVP Thrift Store in particular, can ameliorate the fast fashion business model of excessive production, consumption, and disposal of low-cost clothing, and in so doing, respond more authentically to the cries of both the earth and the poor.

The role of the SSVP within the global fashion industry

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, revenue from the global fashion industry was estimated at between $1.7 trillion and $2.5 trillion (Euromonitor and McKinsey) with the sector also employing over 75 million people (solidaritycentre.org). It will surprise some people to know that the SSVP is a global player in that sector with an estimated network of over 1,600 thrift shops globally, primarily across North America (USA 550, Canada 100), Australia (633), Ireland (230), New Zealand (60+) and England & Wales (50). Thanks to changing consumer behaviour, led by climate activists, ethical shoppers, bargain hunters and vintage collectors, second hand clothing or thrifting as it has become known, is delivering exponential growth globally, with 2027 revenue expected to pass $351 billion dollars (statista.com).

SSVP Thrift Store – So much more than a charity shop

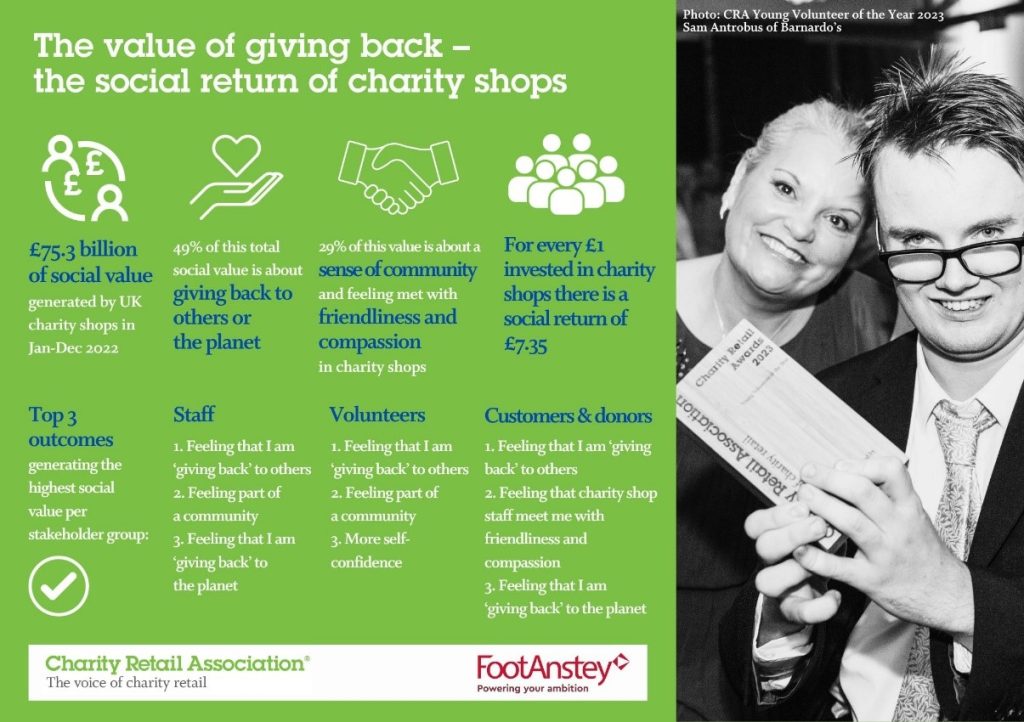

The staff and volunteers who work in our charity shops and indeed those who frequent them as customers or donors, understand their true value as:

- A source of affordable clothing & household items located at the heart of the communities who need them most.

- An ethical and sustainable shopping alternative

- A brand ambassador for SSVP and a gateway to our services

- A community hub for people disconnected from society through poverty or other circumstances creating isolation.

- A welcoming environment for asylum seekers and refugees who can volunteer and make a meaningful contribution to the community they hope to settle in.

- An invaluable community asset that affords all local people the opportunity to volunteer their time or donate preloved clothing or household items.

- A vital fundraiser for SSVP Conferences and Councils

However, a recent study, completed by the Charity Retail Association in the UK, also identified that for every £1 invested in charity shops, £7.35 of social value is generated, creating an additional £75.3 billion pounds sterling of social value across the UK in 2022. This is in addition to over €900 million of income annually across the UK for parent charities.

Environmental and Social Concerns

It isn’t all good news, however! We now know that the fashion industry is also one of the biggest polluters on the planet with the textile supply chain emitting over 3.3 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases annually, (Quantis, 2018), more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined. Climate change is having a devastating impact on global populations with experts projecting that as many as 1.2 billion people (climate refugees) around the world could be displaced by rising sea levels and other extreme weather events by 2050 (The Ecological Threat Register). The carbon footprint of the fashion industry stretches from the over production of fast fashion, mainly in Asia, to the over consumption of clothing across the global north and the export and dumping of clothing in many markets including Africa in a move that has been referred to as “Waste Colonialism”. Ex-Summary-Trashion-_FINAL.pdf (changingmarkets.org)

Pre consumption problems

An estimated 150 billion garments are made annually, mostly in Asia and increasingly from synthetic non-biodegradable materials, in an industry beset by poor working conditions. These synthetic materials are mostly plastic-based polyester, polyamide and acrylic and are now polluting our waterways and indeed our food chain. During this manufacturing process, greenhouse gases like nitrous oxide are released into the atmosphere. Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a type of greenhouse gas that is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide (Overview of Greenhouse Gases |US EPA). The sector also relies mostly on non-renewable resources – 98 million tonnes in total per year – including oil to produce synthetic fibres, fertilisers to grow cotton, and chemicals to produce, dye, and finish fibres and textiles (Ellen MacArthur Foundation)

There are also an estimated 40 million people, mostly women and girls, working long hours and being exposed to harmful substances, including fabric dyes. It is estimated that of 3,500 chemicals used in clothes manufacturing, 750 are harmful.

Over Consumption of Fast Fashion:

Fast Fashion – a term for cheap and low-quality clothing, rapidly produced to meet new trends (earth.org)

The fashion industry, a strong advocate of consumer capitalism, will continue to make cheap and low-quality garments for as long as we keep buying them and we are consuming textiles at an unprecedented and unsustainable level. Consumers, many now digitally enabled, want fashion faster and cheaper than ever before and are bingeing on fast fashion due to its availability and low cost. The global north is now consuming and then discarding more textiles that ever before with an estimated truckload of abandoned textiles being dumped or incinerated every second of every day (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017).

An early proponent of consumerism, advertising pioneer Ernest Elmo Calkins, spoke of “Consumer engineering” and the need to create artificial demand to boost sales. At the heart of this approach was an attempt to convince consumers that the product they had once used had now been used up. A combination of marketing and consumerism has since been used by manufacturers to boost sales by the “planned obsolescence” of perfectly reusable products. Calkins wrote “To make people buy more goods, it is necessary to displace what they already have, still useful, but outdated, old-fashioned, obsolete”.

Post Consumption Problems

In the Republic of Ireland alone it is estimated that 170,000 tonnes of post-consumer textiles are generated annually, with 64,000 tonnes being disposed of through household waste. (www.gov.ie). It is estimated that 44,500 tonnes are sold for reuse whilst 15,000 tonnes are recycled.

It is estimated that across the EU that figure is 5.8 million tonnes or 11kgs of textiles discarded for every EU citizen. (Reuters). From January 2025, EU citizens will be required to dispose of these textiles using charity shops, clothing banks or other donation centres and will not be permitted to place them in domestic waste. This is part of a much wider EU push towards greater circular economy, in line with the UN Sustainable Development goal.

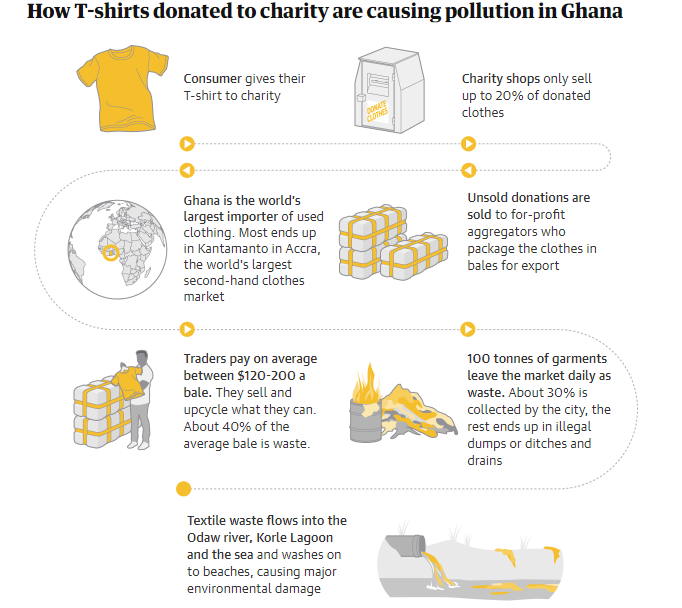

The charity retail sector typically reuses 30% to 40% of donated textiles and sells the remainder to clothing recyclers or exporters. Recyclers in Ireland will grade and then export 80% of available textiles with 15% going for fibre extraction whilst the remaining 5% is sold for Refuge Derived Fuel (RFD). Much of these exported textiles end up in markets across Africa like Kantamanto in Accra, Ghana where an estimated 15 million second hand garments arrive each week, many of them ungraded. It is estimated that up to 40% of imported textiles are unfit for reuse and are then dumped or incinerated, causing pollution to the land, sea, and air. See photo of discarded textiles on Jamestown Beach, Accra.

The Or Foundation has highlighted issues in Ghana, https://theor.org/, whilst Changing Markets has reported widely on issues in Kenya, accusing Western society of engaging in “Waste Colonialism”.

Thinking globally, Acting locally

In addition to being a global player in the second-hand textiles sector, the SSVP is an associate member of UNESCO, a member of Global Catholic Climate Movement, is a Special Adviser to the UN Economic and Social Council and is fully aligned with the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (www.ssvpglobal.org).

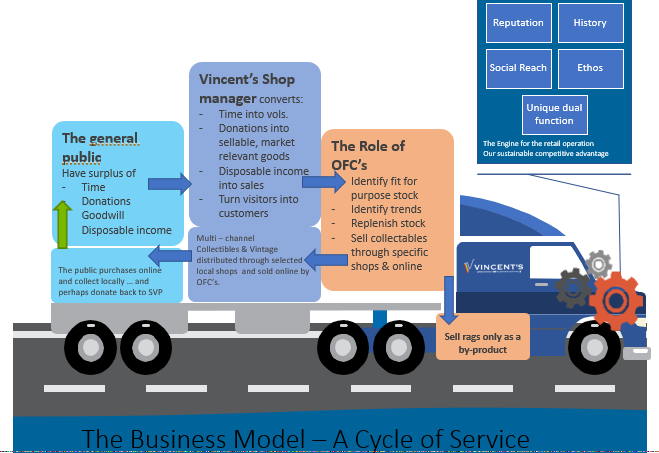

SSVP Thrift Stores (SVP Retail) in Ireland receives between of 15,000 and 20,000 tonnes of donated textiles and has developed a circular business model which includes a network of collection, sorting and redistribution centres for textiles called Order Fulfilment Centres (OFC’s) which will soon be connected to our shops using Electronic Point of Sale (EPOS). That technology will be used to track customer demand across the national shop network and assist in the transfer of surplus stock from other locations to meet that need. This will go a long way to introducing greater circularity whilst fighting poverty in Ireland but is it time that we started to think globally AND act globally?

Future Challenges and Opportunities

Our planet cannot cope with our wasteful culture of “Take, make and throw away”, particularly when it comes to textiles. Charity retail, the network of SSVP Thrift Stores, offers real hope in the fight to slow the harmful effects of fast fashion. In Ireland, and indeed many other countries with charity shops, we are making meaningful progress in keeping clothes in reuse locally, but is it perhaps time to start a conversation about how the SSVP conferences globally can get access to some of the surplus clothing that we, primarily in the global north, are indirectly exporting to their countries, primarily in the global south, via recycling / export companies? If that topic could be meaningfully addressed, SSVP Thrift Stores would truly be responding to the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor.

Pope Francis throws down a challenge to us all in Laudato Si and asks “Is it realistic to hope that those who are obsessed with maximizing profits will stop to reflect on the environmental damage which they will leave behind for future generations? Where profits alone count, there can be no thinking about the rhythms of nature, its phases of decay and regeneration, or the complexity of ecosystems which may be gravely upset by human intervention”.

By Dermot McGilloway, SSVP Ireland

Source: https://www.ssvpglobal.org/

0 Comments