THIGIO, KENYA — Michael Kamau Mathini is convinced that his father lived as long as he did because of the quality of care he received at Our Lady Hospice-Thigio, run by the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent De Paul.

Joffrey Mathini Kamau died in March 2021 at age 106, his son said, having entered the small hospice center in 2014. “My father was at the hospice for a long time,” Kamau said. “He would not have lived as long as he did. The sisters do really good work. Apart from having prostate cancer, he was also blind. He had two wives but they were not able to care for him.”

Terminally ill patients in this quiet farming village in Kiambu County, some 39 kilometers (24 miles) outside the capital of Nairobi, are treated at the nine-bed hospice center established by the sisters in 2010. The idea for the facility arose because of a need the sisters saw in the community.

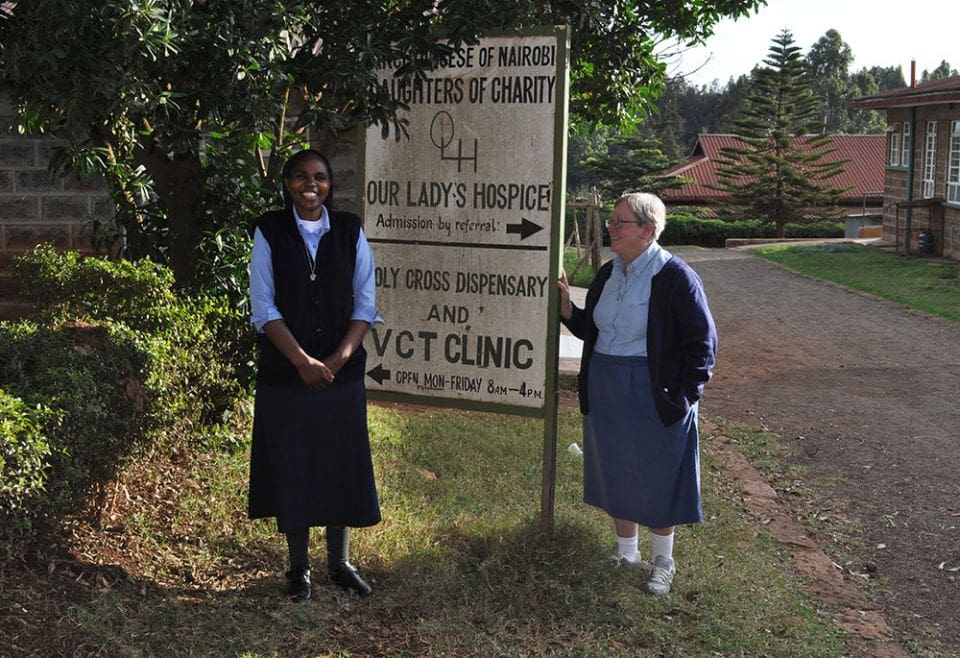

Sr. Mary Mukui and Sr. Deborah Mallott of the Daughters of Charity of St Vincent De Paul outside Our Lady’s Hospice, in Thigio, Kenya. The Daughters of Charity opened the hospice in 2010 and it has provided palliative care to 568 patients and their families. (Lourine Oluoch)

When the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent De Paul arrived in Kenya in 2002, they set up home in Thigio. At the time, there was a great deal of poverty in the area, according to Sr. Deborah Mallott, the administrator of the congregation’s projects in Thigio.

“We are a predominantly farming community with an arid kind of climate. That means that we are constantly fighting drought or flood. A family might get a good crop one year and go two years without, and so they struggle,” she said. “People really, really do struggle. It’s a developing area but there’s still a great deal of poverty.”

The sisters would walk through the neighborhoods, visiting those who were sick. “They found more and more patients who were suffering from serious, sometimes terminal illness that didn’t have anywhere to go at the time,” she said. “In those days there were many, many houses without electricity, without running water. There were people living in one-room houses and it was very hard to care for somebody with HIV or cancer in that kind of a circumstance. That is why the sisters started thinking about doing hospice care in this area.”

The hospice, on a slight hill between a church and the Holy Cross Medical Clinic, has over the years provided palliative care to 568 terminally ill patients. It is one of only 70 facilities in Kenya that offer palliative care to terminally ill patients and their families.

Most of the patients are referred to the hospice from nearby hospitals, while others choose the facility on recommendation of friends and family.

“We admit clients with cancer in stages 3 and 4 and those with HIV/AIDS in the last stages,” says Sr. Mary Mukui, a Daughter of Charity who is also the manager of Our Lady’s Hospice and Holy Cross dispensary. The patients often are aware of their conditions, she said.

“They know its palliative care which is needed and most of them are already in good terms with that, and have somehow accepted what is coming,” she said. “We journey with the family.”

Sr. Eileen O’Callaghan, a nurse and founding manager of Our Lady’s Hospice, opted to spend the last month of her life at the very hospice she had helped establish and run for nine years. When she was diagnosed with cancer in its terminal stages, O’Callaghan, originally from Ireland, decided to stay in Kenya.

“It was her choice to come here because she knew the care is good,” said Elizabeth Wanjiku, a hospice nurse who has worked at the hospice since its founding. “It was hard to see one of us fading away and finally going to the grave, but we gave her the best that we could,” Wanjiku said. O’Callaghan died Sept. 30, 2019.

“She had confidence with the care here,” said Sr. Mary Mukui. “It was hard for the staff seeing her lying on the bed, nursing her but they did their best because she had taught them and given them the best. She was very happy,” says Mukui, a registered nurse as well as the current manager of Our Lady’s Hospice-Thigio.

In addition to the hospice, other projects run by the six sisters of Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent De Paul in Thigio include the Holy Cross Medical Clinic and a physiotherapy unit which provide general health care to the community. Other projects include a program for special needs children and youth, a social lunch program for the elderly, a women development program, a library of more than 2,000 books and a sports program for both girls and boys.

The congregation has 34 sisters in Kenya working in projects in Thigio, Nairobi, Kitale, West Pokot and Kioo-Mwingi.

The hospice works closely with the patients’ doctor to know the details of the person’s illness. The doctors’ prescriptions are followed and if the center doesn’t have the recommended medication, the family is asked to try to buy it and bring it to the hospice.

The idea of hospice care has gained greater acceptance among people in the area, Mukui said. “Some days back they were really afraid of hospice, thinking it’s an area where people just come to die, but over sometime they have realized it is not only for dying but it’s a place where patients are taken care of and they can live for long,” she says.

“Our best advertisement is not the media, but the people who have been our clients,” said Sr. Deborah Mallott. “A family will come and request that their patient be admitted and they’ll say, ‘So-and-so said their mother died here and they told us about this place.’ ”

The coronavirus pandemic initially affected the hospice significantly. Not only did it push up the cost of caring for the patients, but the hospice experienced a drop in the number of patients. That seems to have eased in recent months.

Mallott said she wishes the hospice could receive patients sooner. “Families try their best at curing their patient, certainly, but sometimes they try too long, and the patient goes down too far. If they could bring them earlier then they could have a better quality of life for longer,” she said.

The biggest challenge the hospice faces currently is funding since the National Health Insurance Fund, or NHIF, stopped covering palliative and hospice care, Mukui said. The hospice charges 2,000 Kenyan shillings (about $17) per day to cater for the needs of the patient including nursing care, medication and food.

“In 2019 they stopped covering palliative care and hospice care throughout Kenya,” Mallott said. “Maybe they do something with public hospitals but private hospitals have completely stopped …we hope that NHIF will reconsider and continue to support hospice care, because many of our families cannot afford the 2,000 shillings.”

According to the 2020 annual report of the Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association, or KEHPCA, the Ministry of Health identifies the development of a National Palliative care policy as a key deliverable of the National Cancer Control Strategy 2017-2022 that was launched in 2017.

According to Mackuline Atieno, the executive director of KEHPCA, “NHIF has talked about challenges in reimbursing hospices because of reasons like lack of an expert or a qualified person to quantify the care that they give in the community or the model of care that they give.”

She added that “NHIF has conditions and criteria to be able to charter a facility to become NHIF accredited, which the kind of care provided by the hospices don’t necessarily have.” NHIF should be more “flexible and in their criteria put in the special facilities like hospices because if they withdraw, there is a big gap that is left there and people with life-threatening conditions or longtime support are going to miss out,” she said.

To ensure the hospice keeps running, the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent De Paul works with global and local partners, including U.S.-based Hospice at Home Caring Circle, and Misean Cara in Ireland, that help raise funds for the facility.

“For local donations we have a group called Outburst Limited,” Mallott said. “They found out that several of their members had had their family members here in the hospice and so they took it on to do fundraising for us once a year and they manage to raise usually around Ksh 100,000 [about $882] for us a year. Anywhere we can get funding we do. We look everywhere for funding.”

“We know the hospice is pretty effective because the families come back, even after their loved one has passed away. They keep in touch. They’ll come and visit, they might drop off something that they know that we usually use in the hospice or they might just come to visit the patients,” she said.

Kamau notes that the biggest challenge of having a terminally ill patient is the lack of support for hospice care from the National Health and Insurance Fund.

“Before NHIF would pay for the treatment but six months after my father’s admission to the hospice they stopped. We visited the headquarters several times to get help to no avail,” he said. They had to use all of his father’s money, sell the farm animals and contribute themselves to his care.

“We spent a lot of money but it was all for good,” Kamau said, adding that he was impressed with the quality of care the hospice provided to his father. “They treated him with a lot of dignity,” he said.

The family learned about Our Lady’s Hospice through a referral from the hospital where his father had been receiving cancer treatments. While some family members strongly felt that his father should have been cared for at home rather than by strangers in a hospice center, no one was able to provide the care.

“At home no one would have given him the kind of care that he got at the hospice,” he said. “It is very clean place and there is no bad smell in the wards. The clothes and the blankets are very clean and well taken care of. He also looked clean and healthy. I like the place and everybody appreciated the work of the sisters. He made friends with the workers at the hospice. You would go there and find them telling stories. They called him ‘grandpa,’ ” he recalled.

“It’s a privilege to serve the people especially the sick here and their families,” Mallott said. “We’ve become a part of their families and they have become a part of ours. We deeply care about the people that we serve here. We consider it a tremendous privilege to be able to do this work and to serve God in this way.”

Source & Photos: Global Sisters Report

0 Comments