Homelessness and COVID-19 in an International Context

One of the silver linings of the COVID crisis in the UK is that it could lead to a meaningful reduction in the numbers of people sleeping rough on our streets. Within the first three weeks of lockdown, the government, working hand in hand with the voluntary sector and faith groups, managed to house and cater for 15,000 people in hotels up and down the country, demonstrating that we can end street homelessness very quickly if we have the mind to do so. There is still much to do and the Government’s Task Force, headed up by Dame Louise Casey, has done well to secure enough funding to give everyone an offer tailored to their needs as the hotels begin to decant. Over 6000 new housing units are in the pipeline and there is significant revenue available to support the more vulnerable such as those with drink, drugs or mental health problems . We still need to understand better what will happen to EU nationals trapped in the system and, very crucially, those with no recourse to public funds, but overall we are off to a good start – more on this below.

However, the picture of what is happening to homeless people internationally is very different to the UK, with very variable responses reported. This blog owes much to the work of the Institute of Global Homelessness based at DePaul University in Chicago, which is tracking the impact of COVID on homeless populations. It provides a snapshot of how different countries, systems and cultures are responding. We will not know the full impact of the pandemic on this population for some time but anecdotal evidence points to tremendous suffering in many parts of the world.

Early into COVID-19 lockdown measures, poet and author Damien Barr wrote a poem which became the basis for an oft-repeated phrase: “We are not in the same boat; we are in the same storm.” The aphorism highlights an undeniable reality: that the effects of COVID-19 have not been experienced equally by all people, a dissonance which has roots in many of the ‘usual’ marginalisation crossroads which facilitate structural inequalities, including but not limited to race, poverty, mental illness, and housing.

Guidance for prevention and virus suppression has centered around self-isolation, stringent sanitation and hygiene, and closure of community access points. But what does this mean for people experiencing homelessness who are multiply disadvantaged? Rough sleepers are more likely to be living with mental illness; more likely to be susceptible to viral infection; more likely to belong to marginalized ethnicities, genders, classes and castes; more likely to lack access to hygiene facilities; more likely to be living with food and water scarcity; and, of course, less likely to be able to self-isolate while living and sleeping in outdoor, public spaces.

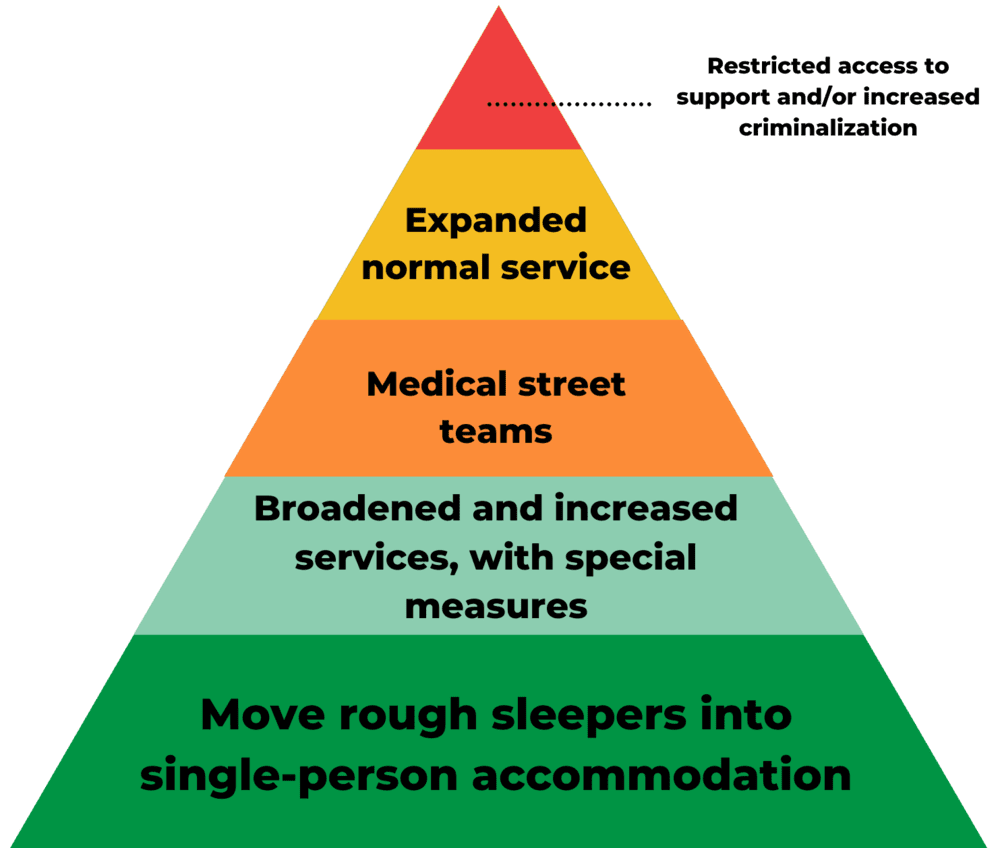

These realities render following general guidance near-impossible, and homelessness services across the globe have had to grapple with the necessity of near-complete system redesigns as COVID-19 guidance evolved. Their ability to adapt and offer appropriate support has varied, and responses have been broad, ranging from no special intervention for rough sleepers to bringing all or almost-all rough sleepers inside during the lockdown period. Most places have struggled to get sufficient protective gear for workers, and found their volunteer base critically cut back as lockdown kept people at home. These responses have taken place at national and city levels, with varying degrees of efficacy, and tend to fall within the following broad categories:

Although responses have been grouped into umbrella categories, it is important to note that national or city interventions do not necessarily fall neatly into any one category, and may have elements from all four, particularly in areas where coordination levels between government and NGOs are low. Additionally, descriptors like “normal service” are meant to indicate a status quo within a specific place rather than a normative definition of what “normal service” is or should be.

Restricted Access to Support and/or Increased Criminalisation

As cities worked to ensure that their populations were obeying stay-at-home orders, people without a home to stay in faced the catch-22 of increased criminalisation for being in public spaces while access to inside spaces such as communal shelters, faith institutions, and soup kitchens were closed :

- Italian police were reported to be issuing fines of $220 with associated prison time of up to three months

- In Brussels and Paris, restricted travel arrangements and the closure of food banks, and meal delivery services led to food shortages even for those in temporary accommodation

- Nigerian officials were reported to be ticketing and arresting people found sleeping rough, and reportedly performing raids on shelters

- Homeless shelters in Manila were closed completely, and reports of tens of thousands of ensuing arrests made for people breaking curfew

- Lack of shelter space in India left many rough sleepers in overcrowded streets without access to shelter, food, and work, causing increased tension with police and leading to reports of returning migrants being sprayed with bleach

- Increased criminalization of homelessness during lockdown measures proved particularly harmful as prison overcrowding and lack of hygiene led to skyrocketing infection rates, particularly in the United States

- The Japanese government’s promise to distribute reusable face masks did not apply to rough sleepers, who had no fixed address at which to deliver them

Expanded Normal Service

At the lowest level of response are cities which offered no special support to rough sleepers as part of measures to combat COVID-19, although most cities expanded the availability of these services. Often this took the shape of additional bed spaces in communal crisis shelters or repurposing buildings to become new communal shelters, a tactic which brought with it the potential of increased risk to exposure due to crowding:

- Hungary made at least 500 extra shelter beds available in Budapest, with plans to repurpose and open additional spaces; however, they made no changes to stringent criminalization laws

- Denmarkdeemed homelessness services “essential,” with municipalities given responsibility for securing shelter for homeless persons

- France announced €65m for emergency housing of 10,000 beds and plans for opening 73 new shelters for sick individuals; they also extended the time frame for their winter program

- Cape Town opened sports stadiums, schools, and other public spaces to create homeless camps — saving rough sleepers from fines but potentially exposing them to increased risk of infection due to overcrowding

- South Korea closed its soup kitchens but opened several new, temporary shelters which provided meal services and provided close monitoring and frequent testing

Broadened and increased shelter service with special measures

Elsewhere, governments expanded existing shelters and services, but made adjustments to operational standards and provided funding to implement additional measures, such as broadening pre-existing housing programs and implementing educational phone lines with linkages to shelter.

- Chile expanded its shelter service and its winter program, which includes medical street teams, with increased focus on sanitation and additional measures being put in place, including education phone lines and reporting systems

- The United States created the CARES Act Emergency Solution Grants, which provided funding for shelter operation, expansion and better spacing of beds; improved the connection with permanent housing; and provided rental assistance

- Barcelona began issuing certificates proving that individuals had no home to go to, exempting them from the threat of fines

- Brazil’s outbreak epicenter, Sau Paulo, opened six new homeless shelters, including one specifically for individuals who tested positive for COVID-19, alongside an expanded food subsidy

- Berlin announced plans to convert hostels into shelters for 350 rough sleepers

Medical Street Teams

The outbreak has seen the addition or expansion of medical street teams as part of most national and city responses to COVID-19 among homeless populations. Where it was not, NGOs like Medecins-Sans-Frontieres have stepped up to supplement local responses.

- In Los Angeles, medical street teams equipped with COVID-19 tests provided people living in encampments with regular health and welfare screenings, counseling and transportation to shelters and hotels

- As part of broader measures taken, New South Wales provided mobile on-street testing teams

- Moscow continued operations on its “Social Patrol” mobile team, which provided base-level healthcare like temperature checks, physical examinations, and free antiseptic bottles; however, no additional services were opened, with some shelters housing as many as 40 people per room.

Moving rough sleepers into single-person accommodation

The most significant, system-wide shifts were made by cities who were able to move most or all of their rough sleepers off the streets as lockdown measures were put in place. This was done typically by requisitioning hotels, hostels, and rental properties for use by rough sleepers and, in some cases, individuals living in overcrowded or precarious housing.

- The UK’s strategy focused on bringing all rough sleepers inside, reporting that housing was found for 15,000 vulnerable people and pledging funding to ensure they do not return to the street

- Various cities in the United States have worked to secure single-person accommodation in hotels, AirBnBs, and rental properties, with varying degrees of success — Los Angeles set a target of 15,000 rough sleepers (about 5% of the total population) to be moved into housing, but have fallen short

- Various territories across Australia partnered with hotels to provide housing for rough sleepers in the form of hotel rooms and hostels

- France promised to secure 7,800 hotel rooms; however, it should be noted that charities have reported that some of these promises have gone unmet

Looking Ahead

What has become increasingly clear over the past six months is that homelessness is, and always has been, an urgent public health crisis — but also that, when given the right tools, it is possible to meaningfully and sustainably address it. Housing is a critical part of healthcare internationally, without which repeated waves of viral outbreaks will be difficult, if not impossible, to prevent. As nations re-open, homelessness systems have begun to look for ways to ensure that services do not return to a status quo, but instead make a permanent shift toward housing-focused interventions.

Nicholas Pleace, Director of the Centre for Housing Policy and Professor of Social Policy at the University of York writes: “We should see an adequate home just as we see medical treatment: as every citizen’s right, not as something that only the rich can afford.”

It’s true. If you think about it, you meet very few rich homeless people.

Mark McGreevy is the Coordinator of the Famvin Homeless Alliance, CEO of the Depaul Group, and founder of the Institute of Global Homelessness.

Molly Seeley is project manager at the Institute of Global Homelessness

This article was originally published in the Centre for Catholic Social Thought and Practice website.

0 Comments