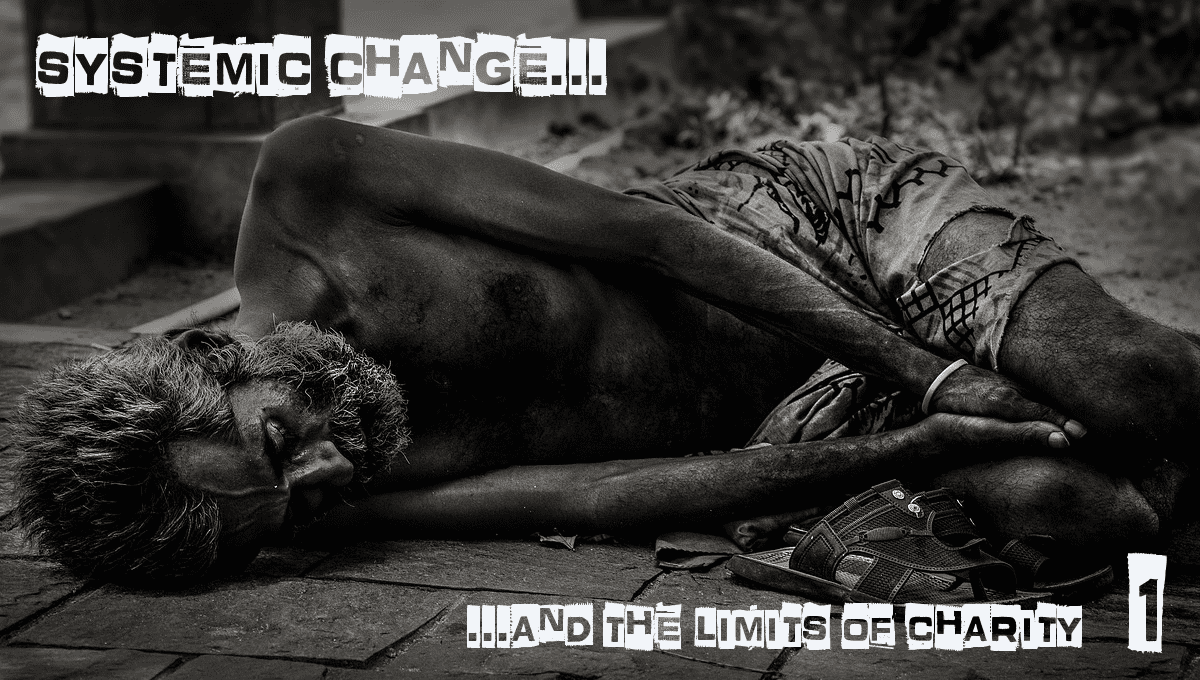

Does charity choke justice? On the Limits of Charity (part 1)

David Hilfiker, a veteran of decades of direct service with the poor, raised questions 15 years ago in a 2001 article from The Other Side magazine exploring the tension between charity and justice. This is the first of a two-part reflection on his writings.

Here are some selections from what he wrote…

Out of my years of working with individuals within a faith community that has many ministries to the poor, I began wondering about the side effects of our charity. Both charity and justice are necessary, but it’s important to know about the ways our charity might work against justice if we hope to ameliorate that impact.”

Do works of charity impede the realization of justice?

To put the question most bluntly: Do our works of charity impede the realization of justice in our society?

This is not a question of our personal commitment to justice. Throughout all of my years in Washington, I have yearned for justice and felt ready to sacrifice for it. I have hoped that my work brings attention to the plight of the poor and thus contributes to justice.

What I actually do, however, is offer help to poor people. Though I believe God calls me to do this, I could leave at any time.

My overall concern is this: Charitable endeavors such as Joseph’s House (ed. A home for people with AIDS that Hilfiker founded) serve to relieve the pressure for more fundamental societal changes.

Something similar certainly happens at Joseph’s House itself. How many of our contributors and volunteers end up feeling that their participation with us fulfills their responsibilities to the poor?

It will not be a conscious thought, of course. But you come down and volunteer for a while, or you write a check, and it feels good. Perhaps you develop a close relationship with a formerly homeless man with AIDS, and you realize your common humanity. You feel a real satisfaction in that. You bring your children.

But in the process you risk forgetting what a scandal it is that Joseph’s House or your local soup kitchen is needed in the first place, forgetting that it is no coincidence your new friend is black, poor, illiterate, and unskilled. It is easy to lose an appropriate sense of outrage.

An illusion that the problem is taken care of

I am also concerned that places like Joseph’s House may reassure voters and policy makers that the problem is being taken care of.

Soup kitchens and shelters started as emergency responses to terrible problems—to help ensure that people do not starve, or die from the elements. No one, certainly not their founders, ever considered these services as appropriate permanent solutions to the problems.

But soup kitchens and food pantries are now our standard response to hunger; cities see shelters as adequate housing for the homeless. Our church-sponsored shelters can camouflage the fact that charity has replaced an entitlement to housing that was lost when the federally subsidized housing program was gutted twenty years ago. Soup kitchens can mask unconscionable cuts in food stamps.

Who is going to do the time-consuming work of changing the system?

If we are busy caring for the poor, who is going to do the time-consuming work of advocacy, of changing the system?

For most of us, the work of advocacy is less rewarding than day-to-day contact with needy people. It is less direct. As an advocate I may never see significant change; I would rather immerse myself in direct service. And so the desperately needed work of advocacy is left undone.

Is privatization the answer?

A more subtle problem is that many social ministries may unwittingly contribute to the perception that governmental programs for the poor are inefficient and wasteful, and are better “privatized.”

The last twenty years have seen a harsh turn against government. People in our society who oppose justice for the poor have used the inevitable organizational problems within some government programs to smear any kind of governmental action. One of their favorite tools is the supposed “efficiency” of nonprofit organizations.

It is true that nonprofits can often do things with relatively little money—primarily because of all the volunteered hours, the donated goods, the low or non-existent salaries, the space donated by churches, and so forth. Government programs do not ordinarily get these enormous infusions of free time and materials, so of course, they are more expensive than ours. But “expensive” is different from “inefficient.”

Only the government—that is, “we the people,” acting in concert locally, state-wide, or nationally—can guarantee rights, can create or oversee programs that assure everyone adequate access to what they need. Because government can assure entitlements while Joseph’s House cannot, comparing the two is not even appropriate. Still, the comparison is used to rail against government action for justice.

And what of charity’s toll on the recipients’ human dignity?

Charity may be necessary, but charity—especially long-term charity—wounds. Try as we might to make our programs humane, it is still we who are the givers and they who are the receivers. Charity thus “acts out” inequality. Sociologist Janet Poppendieck writes that charity excuses the recipient from the usual socially required obligation to repay, which means sacrificing some piece of that recipient’s dignity.

We hear much talk these days about “faith-based organizations” as appropriate tools for dealing with social ills—perhaps even replacing government as the primary provider of services to the needy. But while they may usefully play a role, faith-based organizations cannot be a substitute for government.

Consider, for example, Joseph’s House. In our care for homeless people with AIDS, Joseph’s House depends on the good will of an enormous number of people. We were founded only with the extraordinary support of a nationally known faith community (Washington D.C.’s Church of the Savior), plus the gifts of many people. Even now, local foundations and several thousand individuals and churches across the country provide support, and most of our professional staff have salaries considerably below what they could earn elsewhere. All this is certainly not unique, but it is hardly commonplace.

Our charitable works, then, simply cannot provide care for all who need it. Yet our projects can give the illusion that charity is the solution.

The article which is the source of these reflections first appeared under the title “When Charity Chokes Justice” in “The Other Side” magazine in the September – October 2000 issue on pp. 10 and following.

We invite you to read the full text and share your thoughts.

0 Comments