Doing theology from a garbage dump – learning to make sense of my theology.

Doing theology from a garbage dump – learning to make sense of my theology.

Daniel Franklin E. Pilario, C.M. writes”…on weekends, I help my Vincentian confreres in their parish in Payatas, the biggest garbage dump in Manila. I have been assisting there for around 12 years now. At first, I was invited there to help in giving pastoral care – celebrate Masses or bless the dead, give seminars, meet people. Later, I began to realize that it was not mainly I who was helping. It was in fact they who were helping me make sense of my theology. But that is going ahead of the story.”

Some background and highlights of his story in his own words from a presentation at DePaul University. Here is a link to his powerpoint Rough Grounds and the PDF version Rough Grounds

- The Rough Grounds of Payatas and Elsewhere

No actual census has been done in Payatas, but estimates give you around 40-45 thousand people living around a 16-hectare dumpsite facility. At any given Sunday Mass, no one can tell if someone is a scavenger or not. On an ordinary day, for instance, a scavenger may home with 7-10 dollars in his pocket

But for a theologian like me who shuttles between the dumpsite and the classroom, I am led to ask the question: “How do these rough grounds affect the way that I do theology?” For instance, how do the questions and the painful lives of these people affect the way I think about God, salvation, morality, etc?

Far from being abstract, these questions often spell life and death for millions of people in the margins. And I am not only talking of Payatas, but of 3.8 billion people (half of the world’s population) who live on 2.5 dollars a day as of the latest UN survey.

If the Church still wants to walk the way of Jesus, it needs to listen to them because their lives alone already pose painful questions to the kind of salvation Jesus brings.

- Their Lives as Painful Questions

Most of them only had civil marriages because a church marriage is too expensive and the requirements onerous

They often say, “If the Church does not accept my (marital) situation, I hope God understands me.” I do ask myself: is this the kind of callous Church that I want to serve?

They are cohabitating not because they want to know whether they are compatible or not (as is sometimes in the First World countries), but because they have no choice. These are committed couples.

(These) people on the ground could not really care less about a recent crazy debate on the English translation of the Eucharist (on whether it is “The Lord be with you” or “with your spirit”). To invite Jesus “to enter under my roof” does not resonate at all for peoples who have no roofs over their heads. What a real disconnect!

- Closed Churches

The poor feel that the Church is a rigid, legalistic and “closed” institution.

In another forum on sexually violated women, we invited some survivors to be our resource persons. One of them shared her story: On the day she was raped, she ran to church hoping that someone was there to help. But it was closed. So she ran to the cemetery instead. She read the tombstones and the RIP next to their names. Not knowing much English, she read “rip” and thought this must be “rape”. “Oh my God, ” she said, “they were all raped and they are dead now. Thank you, Lord, I am still alive.” At the end of her talk, what was impressed on us was a simple appeal: “Can you please leave the Church open?” Listening to her, I thought: ” What irony! She found God alive in the cemetery because the Church is closed.” She was talking about the physical church, of course. But metaphorically speaking, the same closed mentalities do abound.

- Closed Theologies

HE then quickly reviews two prominent methods of doing theology that I think are also representative of some others; one of them modern, the other postmodern and the difficulties they have as they address the painful questions.

- Reflexive Theologizing

What is my alternative to get out of these difficulties? In short, I call it “reflexive theologizing”.

The life and death stakes of the poor are absent in their leisurely scholastic world, the world of the observer. At the end of the day, we go back to our well-heated homes and sturdy buildings, to our air-conditioned classrooms and libraries, while these people have to worry all night if their roofs (if they have any) will still be there when they wake up.

To realize this is to step back and tell ourselves that not one of us can have the last word.

If theological theory is limited, we therefore need to open up our method – not only to the working of the Spirit, but also to the voices of praxis from the rough grounds.

For us in Vincentian institutions, this is not a difficult conclusion to make because, like Vincent de Paul, we know that God speaks from the rough grounds of the poor’s lives. For a Vincentian, and for any Christian for that matter, this is the privileged location of God’s presence. I would like to argue that the voices, sentiments, reflections and praxis from the rough grounds are necessary to develop, change, modify or subvert the way we have formulated our doctrines, dogmas and beliefs.

This is not a new thing. The Church has always recognized the sensus fidelium. But when a doctrine is challenged by voices from the ground, the Magisterium and theologians alike close their doors and say, the Church is not “a democracy” or doctrine is not about statistics, etc.

Though I agree that there is something greater about the faith than the results of opinion surveys, these excuses are also used by those in power as alibis not to listen. This explains why I feel ambivalent about the developments of the recent Synod in Rome. On the one hand, all of them agreed that there is a need “to develop a different type of theology in which we can learn from the lived experience of families and the difficulties they are going through”. On the other hand, they are also saying: “we do not intend to change the doctrine; we are only applying it to people”.

I have painstakingly searched throughout the document where the poor – those coming from the rough grounds of Payatas and elsewhere – can participate and be heard. It makes me sad because there is no such mention. Yet it is they to whom the psalm refers and to which we acclaim in our liturgies: “The Lord hears the cry of the poor” (Psalm 34).

- By Way of Conclusion

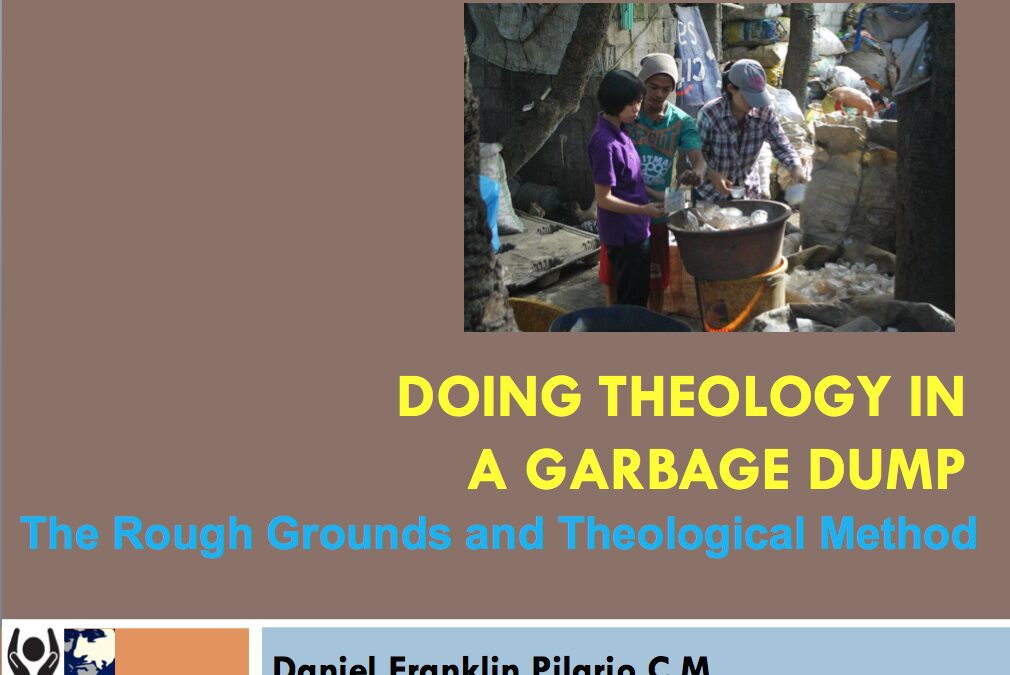

I would like to conclude with the image used in the flyer for this lecture.

It portrays the scavengers sorting out their “catch” for the day – washing the plastic materials one by one, drying the paper and cardboard pieces, piling them up, weighing them so they can get paid by the junkshop owner at day’s end. The lady in violet is a young Indonesian nun who was one of my theology students. In these immersion programs, I usually tell my scavenger friends to teach our students how they work and live. Just that. At the end of one such working day, my scavenger friend shared with me what he jokingly told the young nun: “Sister, you are now good at the work that we do. Should you decide not to pursue your vocation, you can come back here. You’re hired!”

I thought his joke can also offer a perspective on how theology should be done today. The “rough grounds” are not afraid to ask painful questions. And their questions should make us rethink our theologies, revise our options and alter our lives.

Doing Theology – Word

Doing Theology – PDF

| Daniel Franklin E. Pilario, C.M.St. Vincent School of TheologyAdamson University221 Tandang Sora AvenueQuezon City, Philippinesdanielfranklinpilario@yahoo.com | Lecture at the Center for World Catholicismand Intercultural Theology (CWCIT)De Paul University, Chicago23 October 2014 |

Tags: CM, Congregation of the Mission, DePaul University, Featured, Garbage dump, Payatas, Pilario, Theology