“Introducing Père David, the bold priest who brought us gerbils. As a missionary in China, he was also the first westerner to set eyes on a giant panda.” – So writes Christopher Howse in the Catholic Herald.

“Introducing Père David, the bold priest who brought us gerbils. As a missionary in China, he was also the first westerner to set eyes on a giant panda.” – So writes Christopher Howse in the Catholic Herald.

Not mentioned in the article below … Pere David was featured on the cover of National Geographic. He also has a breed of deer named after him.

(About 10 years ago I was privileged to be shown some of his notes and artifacts in the Archives of the Congregation of the Mission in Paris.)

Other famvin articles about him.

—–

Gerbils owe their familiarity in the West to Père David

The first westerner to set eyes on the giant panda was Armand David (1826-1900). He is widely known as Père David, for he belonged to the Congregation of the Mission, founded by St Vincent de Paul.

In 1869, as a missionary in China, based at Muping in Sichuan, he heard tales of a “white bear” in the mountainous forests. It was Père David’s second year in China, and Muping was the remote spot where St Laurent-Joseph-Marius Imbert (canonised in 1984) had founded a college in 1831, before going on to Korea, where he met his martyrdom.

For Père David, the mountains proved as dangerous as the friction between the forces of the Chinese Empire and the prince who ruled the region. Once, after attempting to cross a steep ridge by hanging on to stunted trees in the snow, he and his guide were benighted and lost, as icy rain began to fall.

That would have been the end of them had they not heard distant voices and been rescued by mountain folk who offered them their tree-bough beds in a hut for the night. Père David chose instead to sit before the fire saying his Office. On March 11 of that year, he saw, in the house of a man called Li, the pelt of a panda, with the unlooked-for, but now familiar black and white markings. On March 23, his trackers captured a young live panda, but, to bring it back, they killed it. Père David, who always felt a Franciscan awe at the works of creation, regretted killing animals to provide scientific specimens, but he was obliged to follow the naturalists’ convention of preserving skins, in order to send them to the Natural History Museum in Paris.

At the beginning of April 1869, hunters near Muping brought him a specimen of an adult panda. He noticed that the black markings were less dark than in the juvenile. On April 7 he was brought a live panda, which “does not look fierce, and behaves like a little bear”. To the French, the panda first became known as l’ours du Père David Père David’s bear. More recently, scientists said, no, no, it’s not a bear at all, it should be classified with the raccoons. But in the past generation molecular and genetic studies have convinced taxonomists that the panda is a bear after all, if a strange one.

Two dangers almost prevented Père David’s discoveries ever becoming known. First, the summer humidity in his workshop at the mission station encouraged a plague of hide-eating insects, whatever preservative he used on the skins of unknown animals and birds. Secondly, sickness almost killed the priest.

One fever that laid him low was called “bone typhus” by the local people, and another made his foot swell, keeping him in bed for 12 days and delaying his long walk back to the healthier air of the provincial capital of Chengdu. If he had not been used to walking 30 miles a day in the Alps of his youth, it would have been unlikely that he would have survived his Chinese expeditions.

No wonder the naturalists back in Paris were excited by his discoveries. He sent specimens of 63 species of animal previously unknown, and 65 new species of bird. Besides those, there were countless insects and plants, including dozens of new species of rhododendrons, primulas and mountain gentian.

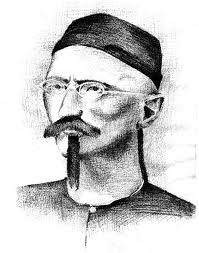

As for Père David, his great ambition had been to dedicate his life to bringing the Gospel to the people of China, or ‘dying while working at the saving of infidels’, as he put it in a letter to his superior at the age of 26. In photographs he is sometimes shown in a close-fitting round cap, pigtail and a Chinese version of moustache and beard classified as a Napoleon II Imperial. He learnt Chinese, and worked with native Chinese priests in the heart of that strange empire.

But among naturalists his three journeys of exploration proved more remarkable: seven months in Inner Mongolia in 1866; two years travelling up the Yangtze and through Sichuan into Tibet from 1868; then, after recuperating, from August 1872 to April 1874 in the mountain provinces of Shanxi and Shaanxi. It had been his inspiring science teaching at the Vincentian college at Savona in Italy that had convinced his superiors to let his talents be directed to biological discovery.

In France Père David is known as a Lazarist, after the mother house where St Vincent lived from 1632, the old priory of St Lazarus. This was sacked by the French revolutionaries on July 13 1789. The site today is marked by a five-storey mural of St Vincent de Paul on the side of the cafe L’Escalier at 105 Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis. In Britain we call them the Vincentians. There are more than 3,000 worldwide, in 86 countries, one of them China.

One native Chinese species that Père David saved by a roundabout route is the deer bearing his name. The Chinese described Père David¹s deer as having ‘the neck of a camel, the hoofs of a cow, the tail of a donkey, the antlers of a deer’. The only herd lived in the Emperor¹s hunting park near Peking. The park wall was breached by a flood in 1895 and many of the deer eaten by starving peasants. The rest were polished off during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900.

But some had been illegally exported to Europe, and the 11th duke of Bedford made it his task to buy survivors and breed them at Woburn. In 1985, 20 were reintroduced into China. There are now more than 2,000 there, not entirely wild, but running free in nature parks.

A more domestic creature also owes its familiarity in the West to Père David – the gerbil. He sent the first small group of “yellow rats” from Mongolia to Paris in 1866. Later, 20 breeding pairs became the parents of all gerbils kept as pets today. Whenever we see a gerbil tunnelling away in its gerbilarium, we can think of Père David, and the fellow members of his congregation who still labour to allow the people of China to find the Gospel in peace.

Christopher Howse is an assistant editor of the Daily Telegraph

This article first appeared in the print edition of The Catholic Herald, dated 9/8/13

Tags: China, CM, Congregation of the Mission