In “Drink Deeply My Daughter” Amanda Kern concludes a reflection on Vincent and Peace with “Vincent teaches us that peace is not words. You won’t find eloquent or flowery words from Vincent about peace. You will, however, find action, which as Vincent shows us, is the only way of truly being a Christian who stands for peace.”

In “Drink Deeply My Daughter” Amanda Kern concludes a reflection on Vincent and Peace with “Vincent teaches us that peace is not words. You won’t find eloquent or flowery words from Vincent about peace. You will, however, find action, which as Vincent shows us, is the only way of truly being a Christian who stands for peace.”

She not only discovers the relevance of his shock and words to scenes from Hotel Rwanda but also recounts the efforts he made for peace as a 68 year old man. Certainly much food for thought as we look at our war torn world in Syria and other places.

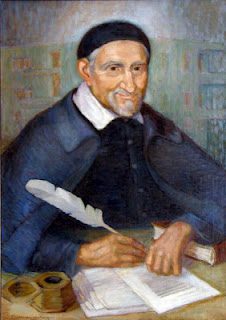

Peace is More than Just Words: St Vincent’s Take on Peace

Saint Vincent de Paul, though, remains mysteriously silent on the topic. He writes (or talks, as in the case of the Conferences to the Daughters of Charity) about everything else under the sun, but nothing specifically on peace or violence – at least, not anything quotable.

I’m currently reading a collection of letters from Dorothy Day, an obvious pacifist, so this bothered me. How could Saint Vincent, the founder of my religious community, really have nothing to say about the topic?

But oh, he did. Only, in typical Vincentian fashion, he did through action, not words.

No tongue can express… no tongue can express nor ear dare to listen to what we have witnessed from the very first day of our visits: almost all the churches desecrated, sparing not even what is most holy and most adorable; vestments pillaged; priests either killed, tortured, or put to flight; every house demolished; the harvest carried off; the soil untilled and unsown; starvation and death almost everywhere; corpses left unburied and, for the most part, exposed to serve as spoils for the wolves.

The poor who have survived this destruction are reduced to gleaning a few half-rotted grains of sprouted wheat or barley in the fields. They make bread from this, which is like mud and so unwholesome that almost all of them become sick from it. They retreat into holes and huts, where they sleep on the bare ground without any bed linen or clothing, other than a few vile rags with which they cover themselves; their faces are black and disfigured. With all that, their patience is admirable. There are cantons completely deserted, from which the inhabitants who have escaped death have gone far and wide in search of some way to keep alive. The result is that the only ones left are the sick orphans, and poor widows burdened with children. They are exposed to the rigors of starvation, cold, and every type of misery and deprivation (CCD., IV:151-152).

As I read this, I can imagine Vincent’s shock upon arriving that first day. I can imagine him writing with a shaky quill, still re-playing those memories from that first day, and the words not coming. You can hear his shock “no tongue can express nor ear dare to listen to what we have witnessed from the very first day of our visits…” He knew that no one could understand their misery unless they saw it with their own eyes as he did; he even wrote to Pope Innocent X “they must be seen and ascertained with one’s own eyes” (CCD., IV:446)

He knew that, not only did the war-ravaged poor need priests (both for material and spiritual aid) but they also needed someone influential to plead for peace. And so, Vincent, a friend to both the rich and the poor, did just that. Not only did he write (including to Pope Innocent X), but he also traveled, meeting directly with the rulers themselves who could bring peace. Travel in a war-torn country wasn’t too easy nor safe in the seventeenth-century but Vincent, in a holy stubbornness, was determined. On one such trip, to plead with Anne of Austria, Vincent’s carriage was attacked by villagers with pikes and guns. If one of the villagers hadn’t recognized Vincent as his former pastor and stopped his companions, Vincent’s story may have ended there. Later in the journey, he encountered a flooded river – his only means of reaching Anne of Austria. But as I said before, he was determined so the elderly 68-year old Vincent got on his horse and forded the river.

There is no way to determine if Vincent’s words brought any peace, but he knew that it was something he had to do. Because of what he first saw in the war-torn areas, he was now committed to the pathway of peace. Not only did he send Vincentian priests to serve there, he also organized relief efforts for the victims of war among the rich and influential he knew – he created leaflets containing their stories and distributed them in parishes all around Paris. Vincent organized a relief effort very similar to how Catholic relief organizations gain collections today. He provided seeds, axes and other farming tools to the war victims, explaining “in this way, they will no longer be dependent on anyone, if some other disaster occurs which could reduce them to the same wretched state.”

Throughout his work for peace, plagued by the misery of those affected by the war, by their starvation, by their illnesses, by the destruction, he wrote words that still resonate today and words that truly show how the war-torn poor had indeed traveled to the core of his heart and soul:

After that, what can be done? What will become of them? They must die: I renew the recommendation I made, and which cannot be made too often of praying for peace…. There’s war everywhere, misery everywhere, In France, so many people are suffering! O Sauveur! O Sauveur! If, for the four months we’ve had war here, we’ve had so much misery in the heart of France, where food supplies are ample everywhere, what can those poor people in the border areas do who have been in this sort of misery for twenty years? Yes, it’s been a good twenty years that there’s always been war there; if they sow their crops, they’re not sure they can gather them in; the armies arrive and pillage and carry everything off; and what the solider hasn’t taken, the sergeants take and carry off.

After that, what can be done? What will become of them? They must die. If there’s a true religion … what did I say, wretched man that I am …! God forgive me! I’m speaking materially. It’s among them, among those poor people that true religion and a living faith are preserved (CCD., IV:189-190).

(I owe much thanks to Fr John Freund’s response to my email, in which I asked about the Vincentian response to war and violence, and his research (you can also search “peace” on famvin), including David Carmon’s study on Vincent and Peace)

Tags: Amanda, Drink Deeply, peace, Vincent, violence, War