El Salvador Sisters See Hope, Work for Change in a Still-Violent Society

During the height of the Salvadoran Civil War, right-wing militias dumped body parts at the gate of a school run by a group of Dominican sisters in the town of Suchitoto.

Located in a contested area of fighting between government militias and leftist rebels, the Dominicans knew the grisly action was meant as a threat and an act of intimidation. This was 1980 — the year in which Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero was assassinated and four American churchwomen were murdered and raped by National Guardsmen.

A mural at the onetime Dominican compound in the city of Suchitoto depicts the desire for peace in El Salvador. (GSR / Chris Herlinger)

The U.S.-backed Salvadoran military had declared war on the church for its advocacy on behalf of the poor, and the Dominican sisters left nine hours after the gruesome discovery. They didn’t return. For a quarter century, the school and its chapel were left abandoned.

“This chapel has heard the cries of the people,” Sr. Peggy O’Neill, a Sister of Charity of St. Elizabeth, said on a cloudless August afternoon as she surveyed the chapel as it undergoes a transformation into a performing arts space for young people and a center for peace called Centro Arte para la Paz (Center of Arts for Peace). A cornerstone of the space, as well, is a museum focused on the events of the Salvadoran Civil War.

The onetime compound of Dominican sisters in Suchitoto, El Salvador, has been transformed into a museum about the Salvadoran Civil War, as well as a planned performing arts space and a center for peace. (GSR / Chris Herlinger)

A resident of El Salvador since 1987 and a onetime member of the pastoral team of Santa Lucia Parish in Suchitoto, O’Neill directs the center, which was founded in 2005 and is a locally based nonprofit.

“This is a peace center using the arts to heal us from the war, and the violence that persists here in El Salvador and all over the world,” O’Neill said. “It is healing space and opens our imaginations to build a spirituality of nonviolence. This is an embedded longing of our people. We know that the power of hope and love will bring peace.”

O’Neill sees hope and change around her: not only with the museum and arts center but for the entire city of Suchitoto, whose colonial architecture and charm are turning the community, located about 30 miles north of the capital of San Salvador, into a tourist destination.

To O’Neill, a native of Jersey City, New Jersey, the transformation of a war-torn community is a balm — proof, she said, that any country’s history “is larger than a war.”

“The story here is large,” she said. “It’s rich.”

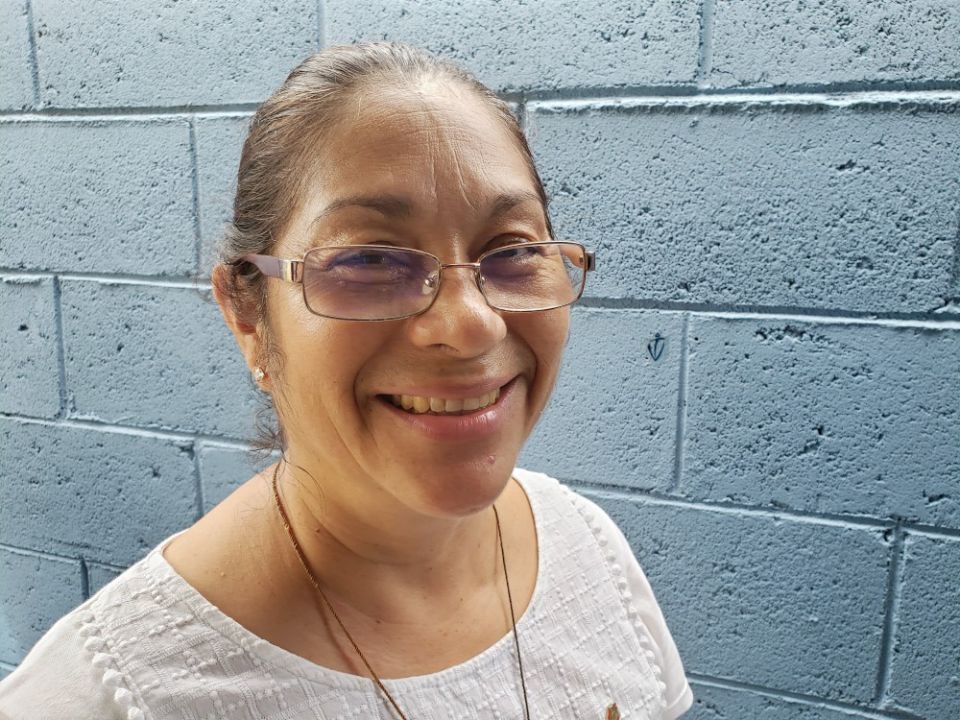

Sr. Peggy O’Neill, a Sister of Charity of St. Elizabeth, at the museum in Suchitoto that examines the history of the Salvadoran Civil War (GSR / Chris Herlinger)

Yet healing takes time, “as does the journey of justice,” she said, which is why even an optimist like O’Neill knows that the division of history into eras isn’t always clean or neat. Once a symbol of Central America’s wars during the last decade of the Cold War, El Salvador is now a symbol for other challenges: gangs and immigration in particular, as well as frustrated hopes about a stalled economy.

The country is also feeling the effects of a three-year drought, with resulting food insecurity — the inability of people to access food — now common, especially in rural areas, said Holly Inurreta, Catholic Relief Services’ country representative in El Salvador. “Food insecurity already exists and families’ abilities to fight against that is eroding,” she said in an interview with GSR.

A crippling combination of bad weather, economic woes and street violence are forcing people to leave and head north in hopes of a better life, either to Mexico or the United States.

“You try to make it work. But when you can’t, you look to leave,” Inurreta said of the combination of challenges. “It pushes people to leave. Families just can’t catch their breath.”

And the society itself has had difficulty in catching its breath: According to the Center for Justice & Accountability, at least 75,000 people died in the 12-year Salvadoran Civil War that began in 1979 and ended in January 1992. But the “social fabric destroyed in the civil war was never really repaired,” said Inurreta.

Moreover, the “violence of the civil war was replaced by the violence of the gangs,” she said, noting a grave problem for the country and a key reason why so many are desperate to leave.

In its most recent annual country report on El Salvador, the New York-based Human Rights Watch said that gangs continue “to exercise territorial control and extort residents in municipalities throughout the country.”

Among their crimes? “They forcibly recruit children and subject some women, girls, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals to sexual slavery,” the report said. “Gangs kill, disappear, rape, or displace those who resist them, including government officials, security forces, and journalists.”

Adding to the problems, Human Rights Watch said, is that security forces “have been largely ineffective in protecting the population from gang violence and have committed egregious abuses, including the extrajudicial execution of alleged gang members, sexual assaults, and enforced disappearances.”

The roots of gangs

Some argue that the gang situation has echoes and roots in the civil war. Canadian political analyst Norma Roumie, in a 2017 paper published in The Great Lakes Journal of Undergraduate History, argues that with the support of the Salvadoran military, the United States “created a foundation for a culture of violence,” and that migration of many young Salvadorans to large urban centers in the United States, such as Los Angeles, placed them at the margins of society, with many turning to crime.

Marginalization, Roumie argues, led to the growth of gangs such as MS-13 and M-18, with the result reverberating in El Salvador when gang members with criminal records were deported back to the country. The massive influx of such deportees was a strain on “a society still dealing with the effects of the civil war and a government lacking the institution to govern properly,” Roumie wrote.

For O’Neill, the U-S.-funded militarization in the 1980s was deeply troubling. “There were things we were hiding behind, like the fear of communism,” she said of the U.S. role in El Salvador.

But she said continued militarization in El Salvador is equally alarming. “The model is still like a war,” she said. “It’s still like a civil war, though now it’s between the police and the gangs.”

“We say ‘post-peace accords,’ but not ‘peace,’ ” she said. “The war never really ended.”

For Salvadoran Sr. Hilda Alfaro, a member of the Guardian Angel congregation, El Salvador’s history is both challenge and opportunity. She believes many Salvadorans “don’t keep track of our history,” and have even opted to forget it in hopes of moving on without a real reckoning of the past.

For Salvadoran Sr. Hilda Alfaro, a member of the Guardian Angel congregation, El Salvador’s history is both challenge and opportunity. (GSR / Chris Herlinger)

Her own experiences illustrate the complexities of El Salvador’s history. Alfaro, 52, grew up listening to Romero’s homilies on the radio, and the slain cleric remained a hero to her and her family. But like tens of thousands of Salvadorans in the 1980s, she and her family fled to the United States. Arriving in Los Angeles in 1985 when she was 17, Alfaro eventually studied social work at California State University, Los Angeles. She took her vows at age 28 after working in Los Angeles County jails and coming to admire the work of sisters there.

Alfaro, who holds dual citizenship and has worked in both the United States and El Salvador, believes the gang problem “didn’t come from nothing” — pointing out the larger historical and social context, illustrated by an oft-heard figure in El Salvador that the United States spent $1 million a day to support the Salvadoran military during the height of the Salvadoran war.

While unclear if that is an exact figure, a 1991 report by the Rand Corporation, a California-based think tank that provides analysis to the U.S. Armed Forces, noted that the United States made a substantial investment in El Salvador during the war, calling it “the most expensive American effort to save an ally from an insurgency since Vietnam.”

The report noted that El Salvador had received over “absorbed at least $4.5 billion, over $1 billion of which [was] in military aid.” Including other credits and investments by the Central Intelligence Agency, the total expenditure “approaches $6 billion.”

At the time, the report said, only “five countries received more American aid each year than El Salvador, a nation of 5.3 million people.”

In short, militarization is a huge dynamic in the country, Alfaro said, including the current challenges of the gangs. “A gang member is someone who has not found opportunities,” she said. “They are human beings looking for [meaningful] life.”

She finds in El Salvador’s tragedy seeds of its hope. “El Salvador is unique because of its history,” she said. “There is a lot of life, a lot of hope. Romero used to say, ‘Honor the name for what it is — El Salvador, the savior.’ ”

“It’s a blessing in a way.”

A movement ‘about joy’

For Alfaro and other Guardian Angel members, that blessing concretely means working with youth in communities affected by gang activity and violence, such as Apopa, a community about 10 miles north of San Salvador.

With backing from the Minneapolis-based humanitarian organization Alight, formerly the American Refugee Committee, and with support from Salvadoran and American businesses, women religious in El Salvador are improving conditions in challenging communities like Apopa with programs to provide safe spaces for young people. The umbrella for this work is called the Color Movement, which Alight describes as being “about joy, shining a light on abundance in El Salvador.”

One of the participants in the Color Movement is 19-year-old Javier Zelada, who started coming to a sister-run youth center in Apopa when he was eight and grew to become a leader among his peers by, among other things, coaching soccer for other young people. (Courtesy of Alight)

One of the participants in the Color Movement is 19-year-old Javier Zelada, who started coming to a sister-run youth center in Apopa when he was 8 and grew to become a leader among his peers by, among other things, coaching soccer for other young people.

In late August, Zelada said goodbye to the sisters and friends as he departed San Salvador to participate in a one-year intercultural program in Duisburg, Germany.

He says he has every intention of returning to El Salvador, attending college and doing something meaningful for his country. Zelada credits Alfaro and the other sisters he knows at the youth center for expanding his view of his country — for coming to understand the significance of Romero’s place in Salvadoran history, for example.

“The history is taught in a very superficial way in school,” he said. “If it weren’t for the sisters, I wouldn’t know our history.”

To O’Neill, who has also worked with the Color Movement, the promise of young people to better their country remains tangible — nearly half of El Salvador’s population is 24 or younger, and young people like Zelada remain the country’s best hope, she and other sisters say.

“El Salvador is full of wonderful young kids who are yearning for bigger things,” she said.

And bigger things are part of the country’s DNA, O’Neill argues.

She points out that the gate at the Dominican compound is now open, welcoming visitors without fear, the memories of a war not fully buried but at least stilled. On a beautiful summer day, the shadows of war seem distant indeed.

These days, O’Neill is preoccupied with the ongoing renovation of the chapel — “new columns, new roof, new walls,” she said.

Reconstruction, piece by piece — just like El Salvador itself.

A mural on a wall outside a youth center in Apopa, El Salvador, depicts Archbishop Óscar Romero, left, and Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande. The youth center is part of a project of sisters and others called the Color Movement. (GSR / Chris Herlinger)

To O’Neill, what emerges in El Salvador now is larger than any war. Salvadorans, she said, “have wisdom sources. Their friends are the friends of God like Rutilio Grande [a Jesuit priest and friend of Romero’s who was killed in 1977 for his work with the poor] and Óscar Romero.”

In those and other examples, she said, Salvadorans have discovered a basic truth: “To be human is to feel your own pain and the pain of others.”

“It’s walking with dignity,” O’Neill said of her adopted country. “That’s what I mean by faith.”

And in the journey of faith, she said, “it is our task to realize we are all connected by our stories and our wisdom sources and the life force we call God that connects us all.”

Author: Chris Herlinger

Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent.

Source: https://www.globalsistersreport.org/

0 Comments