Criminalizing homelessness – a growing phenomenon… But not a new one. St. Vincent de Paul was well acquainted with this. It his time it was called the “Great Confinement”

Criminalizing homelessness – a growing phenomenon… But not a new one. St. Vincent de Paul was well acquainted with this. It his time it was called the “Great Confinement”

Noted Vincentian historian Ed Udovic writes about 17th century France …

“This war … was a war which would be fought against an enemy within the borders of France itself, it was a war that was declared against the poor of France. This declaration of war, which was issued in the form of a royal decree read in part:

We expressly prohibit and forbid all persons of either sex, of any locality and of any age, of whatever breeding and birth, and in whatever conditions they may be, able-bodied or invalid, sick or convalescent, curable or incurable, to beg in the city and suburbs of Paris, neither in the churches, nor at the doors of such, nor at the doors of houses nor in the streets, nor anywhere else in public, nor in secret, by day or night … under pain of being whipped for the first offense, and for the second condemned

to the galleys if men and boys, banished if women or girls.’

This new phase of the long war that was waged by the French state against the most impoverished, powerless, marginalized, and abandoned of its own subjects could aptly be described as the “War of the Great Confinement.”

The royal prohibition against all forms of public begging by the countless numbers of the destitute poor of the city of Paris was accompanied by a strict prohibition against all private almsgiving to these beggars. These measures against both begging and private almsgiving were designed to facilitate the creation of what can only be described as a system of “apartheid” which legislated the forced and punitive institutionalization, or confinement, of the poor in a series of specialized institutions of state control, charity, and profit, which came to be known as the General Hospital of Paris.

Fast forward to 21st century America (and indeed other countries)….

In 33 U.S. Cities, It’s Illegal to Do the One Thing That Helps the Homeless Most describes the situation.

The news: In case the United States’ problem with homelessness wasn’t bad enough, a forthcoming National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH) report says that 33 U.S. cities now ban or are considering banning the practice of sharing food with homeless people. Four municipalities (Raleigh, N.C.; Myrtle Beach, S.C.; Birmingham, Ala.; and Daytona Beach, Fla.) have recently gone as far as to fine, remove or threaten to throw in jail private groups that work to serve food to the needy instead of letting government-run services do the job.

Why it’s happening: The bans are officially instituted to prevent government-run anti-homelessness programs from being diluted. But in practice, many of the same places that are banning food-sharing are the same ones that have criminalized homelessness with harsh and punitive measures. Essentially, they’re designed to make being homeless within city limits so unpleasant that the downtrodden have no choice but to leave. Tampa, for example,criminalizes sleeping or storing property in public. Columbia, South Carolina, passed a measure that essentially would have empowered police to ship all homeless people out of town. Detroit PD officers have been accused of illegally taking the homeless and driving them out of the city.

The U.N. even went so far as to single the United States out in a report on human rights, saying criminalization of homelessness in the United States “raises concerns of discrimination and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”

“I’m just simply baffled by the idea that people can be without shelter in a country, and then be treated as criminals for being without shelter,” said human rights lawyer Sir Nigel Rodley, chairman of the U.N. committee. “The idea of criminalizing people who don’t have shelter is something that I think many of my colleagues might find as difficult as I do to even begin to comprehend.”

Meanwhile, the programs in place to support the homeless are typically inadequate, making claims that ending food-sharing is for their own good specious at best. According to government data, about 600,000 people are homeless on any given night. Some 20 states bucked a nationally declining homeless rate from the height of the recession, increasing in measures of homelessness from 2012-2013. According to the NCH, one survey of homelessness found 62,619 veterans were homeless in January 2012. Other at-risk groups for homelessness include the seriously ill, battered women and people suffering from drug addictions or mental illness. The economy isn’t helping. More Americans live in poverty than before the recession began in 2008 and the number of households living under the poverty line has reached levels unseen since the 1960s.

Some city officials, like Houston’s Mayor Annise Parker, claim that “making it easier for someone to stay on the streets is not humane” and say that uncoordinated charity efforts “keep them on the street longer, which is what happens when you feed them.” A local Food Not Bombs activist told VICE that the actual effect was to intimidate local residents from giving out food. Other cities are harsher. In 2011, more than 20 members of Food Not Bombs were arrested in Orlando for sharing food. Love Wins Ministries in Raleigh was threatened with arrest for providing biscuits to the homeless. Daytona Beach fined, harassed andthreatened jail time for Debbie and Chico Jimenez, who run a ministry called “Spreading the Word Without Saying a Word.”

“Homeless people are visible in downtown America. And cities think by cutting off the food source it will make the homeless go away. It doesn’t, of course,” NCH community organizing director Michael Stoops told NBC News. “We want to get cities to quit doing this. We support the right of all people to share food.”

“Nobody would suggest that the ideal situation for a homeless person to be in is living on the street, but the reality is people are living there and they will die there if they don’t receive food,” National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty policy director Jeremy Rosen toldVICE.

Why you should care. This is cruelty at its basest and most pointless. The homeless are real people who deserve to be treated like human beings. And if a city bans sharing the necessities of life with them, it doesn’t bode well for other ways they treat the homeless.

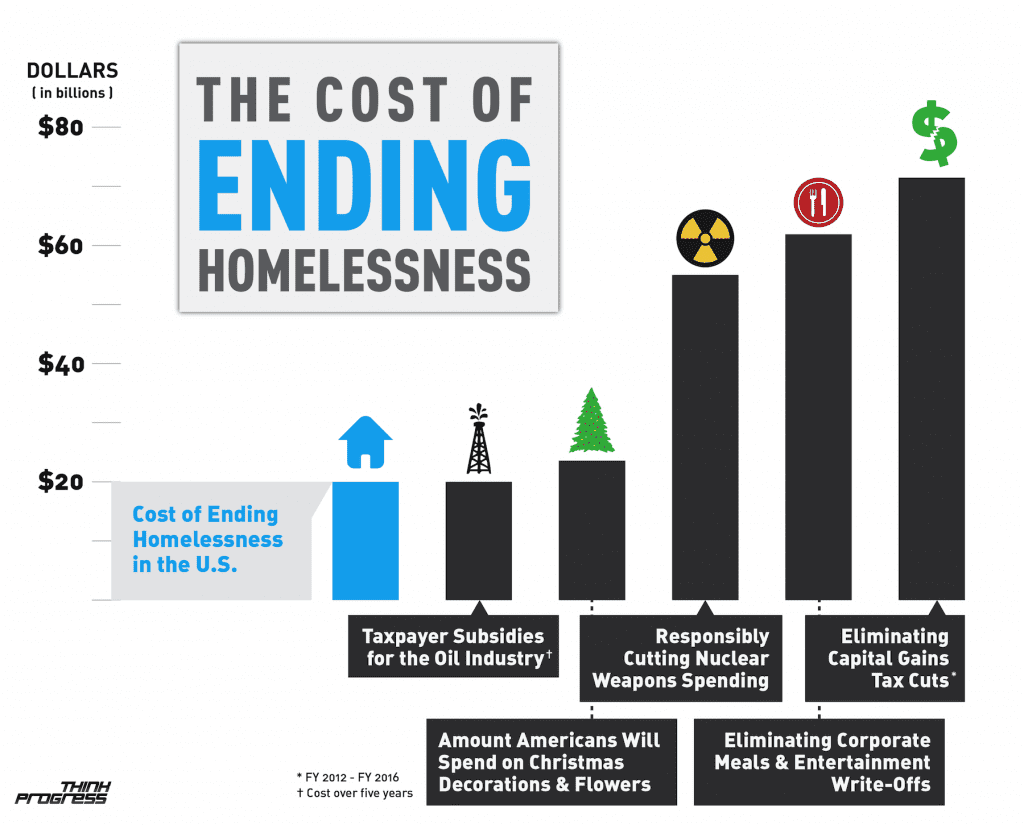

Meanwhile, successful programs have demonstrated that systematically providing housing and food for the homeless costs society less than leaving them on the street.

Tags: Advocacy, Anti-poverty strategies, Homelessness, Udovic