Why We Need to Canonize More Lay Saints

Why We Need to Canonize More Lay Saints

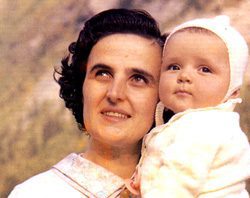

Ever since the Second Vatican Council spoke of the “universal call to holiness,” there has been a move to recognize more lay men and women as saints, as models of sanctity for lay Catholics. Several contemporary saints have already been raised to the “glories of the altar,” among them St. Gianna Molla (1922-1962) [member of the Society of St. Vincent dePaul], an Italian mother (pictured here) who carried a child to term rather than consenting to an abortion, and who died in the process. Others are on their way include Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati (1901-1925) [member of the Society of St. Vincent dePaul}, the charismatic Italian social activist who once said, “Charity is not enough; we need social reform.” In that same vein is the redoubtable Dorothy Day, the American-born co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, whose cause for canonization has just been advanced. And in 2008, Louis and Zélie Martin, the devoutly Catholic parents of St. Thérése of Lisieux (and her equally pious sisters) were beatified in 2008, the rare instance of a husband and wife recognized together.

But when it comes to recognizing saints, the church still tends to favor popes, bishops, priests and members of religious orders. Last month, Pope Benedict XVI released the latest list of 27 candidates for sainthood, which consisted of: martyrs in the Spanish Civil War, including a bishop and 13 Daughters of Charity; an Austrian priest killed in Buchenwald; the Mexican foundress of a women’s religious order; an 18th-century Italian diocesan priest and a Dominican priest who founded the Bethany community. While there are plenty of holy Fathers and Mothers on that list, where are they holy mothers and fathers?

Fifty years after Vatican II, in the midst of the church’s continued invitation for lay people to lead holy lives, why are there still relatively few role models for the laity?

Many lay people have told me, over the years, that they long for a saint who lived a life of extraordinary holiness in ordinary situations. That is, a layperson other than a saint from the very earliest days of the church (St. Joseph); someone who wasn’t royalty (like St. Elizabeth of Hungary); someone who didn’t end up in a religious order at the end of his or her life (like St. Bridget of Sweden); someone who didn’t initially plan to live as “brother and sister” while married (like Louis and Zélie Martin); someone who didn’t found a religious order or social movement (like Dorothy Day); and someone who didn’t die in terrible circumstances (like St. Gianna Molla).

While Catholics recognize that the canonized saint needs to have lived a life of “heroic sanctity,” many long for someone who they can hope to emulate in their daily lives. Which raises an important question: Who is holier–Mother Teresa or the elderly church-going mother who cares for decades for an adult child who is autistic? Pope John Paul II or the pious educator who serves as a director of religious education in an inner-city parish, while holding down another job to support his family? The answer: they’re both saintly, in their own ways. As Blessed John XXIII said about St. Aloysius Gonzaga, the 16th-century Jesuit, “If Aloysius had been as I am, he would have become holy in a different way.” (And not to put too fine a point on it, but that’s still a pope talking about a member of a religious order.)

“Heroic sanctity” comes in many forms—and it includes those whose faith inspires them to found a religious order, and those whose faith enables them to care for a sick child for years on end.

Currently there are three reasons that frustrate the desire for more lay saints of any stripe. …. See full article in America Magazine.

If the church hopes to offer relevant models of holiness for lay people, it’s time to make the canonization process far more accessible, and far less expensive, for those who knew a holy husband, wife, mother, father, friend or neighbor. Santi subiti!

James Martin, SJ

Tags: Laity, Vincentian Family Blesseds, Vincentian Family Saints